Was I sorry, at the time? No. In this world you don’t survive by feeling sorry. You protect your own. You send messages. You build your reputation, not on words, but on what people believe you’ll do if they cross you. Regret don’t buy respect. But later, much later, when the noise dies down and you’re sitting alone with ghosts, yeah, you think about it. You wonder if things could have gone different, if maybe, just once, someone could have reached for mercy instead of a gun. But that’s the kind of thinking that gets a man killed. In my world, you don’t last if your trigger finger hesitates. So was I sorry? Maybe. But not enough to stop.

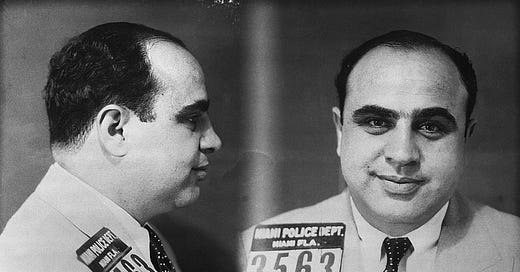

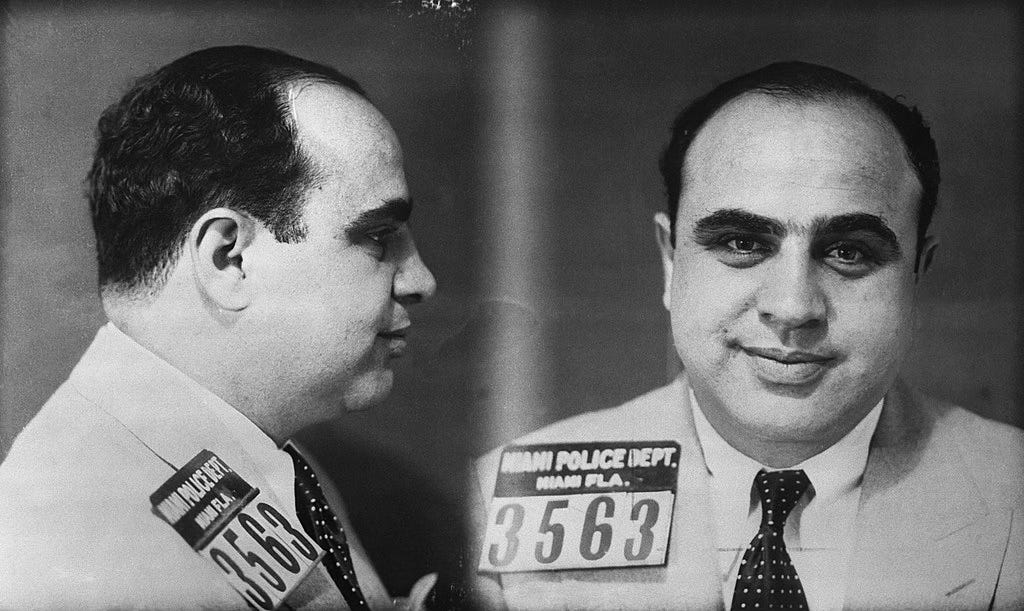

These are the final words we hear in Bob Dylan’s latest Instagram post, in a voice that sounds a lot like Marlon Brando. The clip is titled “Al Capone in his own words: Part 1 of 3.” Capone has just recounted the facts around his first murder, as an up-and-coming mobster on the streets of Brooklyn.

Here we are again, down at the bottom, thinking about mercy and death. In my post of two weeks ago, “Mary Jo, Vlad, Nick Cave and Papa Too,” I discussed Dylan’s tweet from the fall, praising Nick Cave’s song “Joy.” I wrote about how in that song, the Australian singer, finding himself alone with the ghost of his deceased teenage son, jumps up like a rabbit, falls on his knees, and calls out for mercy. In doing so, he discovers that he might still have a capacity for joy.

Also in that post, I pointed out how in Chapter Three, “The Bleedin’ Heart Disease: Finding Mercy with Brando, Down in the Boondocks of Key West,” I discussed Dylan’s many allusions to the virtues of mercy and compassion in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).”

And in my last essay, “Heartbeat,” I showed how young Lorrie Collins, while performing on Ranch Party, had a very human kind of mercy in mind:

My baby is the rare kind

He really sends chills up my spine

My baby loves me yes indeed

My baby is the one for me

MMM, Mercy!

What my baby does for me, me, me!

With his clip of Al Capone, Dylan is continuing the conversation. He’s also continuing a science project he began in “My Own Version of You”:

I’ll take the Scarface Pacino and the Godfather Brando

Mix ‘em up in a tank and get a robot commando

If I do it upright and put the head on straight

I’ll be saved by the creature I create

Dylan’s AI “robot commando” voice is at least two parts merciless gangster, with Scarface Pacino and Brando’s Vito Corleone. But Dylan’s use of Brando’s voice also alludes to the actor’s character in On the Waterfront, as cited by Dylan in “Murder Most Foul”:

Play Down in the Boondocks for Terry Malloy.

Chapter Three has the full story, but here’s a few key points: Malloy is a former boxer who unwittingly plays a part in a murder of another dockworker, Joey, who had agreed to testify about union corruption to the Crime Commission. Terry is slowly awakened to his culpability by Joey’s sister Edie, who radiates love and compassion, and by the social justice preaching of Father Barry. In a eulogy for another murdered dockworker, Barry tells Malloy and his co-workers that any man who remains silent about Joey’s death and the second murder, “shares the guilt of it just as much as the Roman soldier who pierced the flesh of our Lord to see if he was dead.” This is a reference to the New Testament verse that gave rise to the devotion of the Sacred Heart, “that bleedin’ heart disease.” Malloy eventually repents his sins and agrees to testify to the Crime Commission about the killing. He asks for mercy from his brothers on the dock, from Edie, and from God.

We’re also “down in the boondocks” in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

McKinley hollered - McKinley squalled

Doctor said McKinley - death is on the wall

Say it to me if you got something to confess

I heard all about it - he was going down slow

Heard it on the wireless radio

From down in the boondocks - way down in Key West

In summary: we see Nick Cave on his knees in his son’s bedroom, crying out for mercy, Brando as Terry Malloy begging for forgiveness, and McKinley, going down slow from gangrene, confessing to the Doctor. As you’ll recall from Chapter One, “The Underground Stories of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),”” his confession took the form of a hymn: “Nearer My God to Thee.” Jimmy Oden’s “Goin’ Down Slow” is also a plea for atonement at the time of death, in which the singer asks:

Please write my mama

Tell her the shape I’m in

Please write my mother

Tell her the shape I’m in

Tell her to pray for me

Forgive me for my sins

On Dylan’s Instagram, in contrast, we hear Al Capone justifying his killing with only a twinge of remorse.

All the important messages in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” are delivered by song. “Down in the Boondocks”—where Billy Joe Royal also cried out for mercy in the mid-60s—the narrator hears about McKinley’s death and confession on the radio. In Chapter One, I included this quote from Chronicles:

Folk songs were the underground story. If someone were to ask what’s going on, “Mr. Garfield’s been shot down, laid down. Nothing you can do.” That’s what’s going on.

Dylan also tells us that folk music is “reality of a more brilliant dimension,” and “life magnified.” And he writes about Al Capone:

The folksingers could sing songs like an entire book, but only in a few verses. It’s hard to describe what makes a character or an event folk song worthy. It probably has to do with a character being fair and honest and open. Bravery in an abstract way. Al Capone had been a successful gangster and was allowed to rule the underworld in Chicago, but nobody wrote any songs about him. He’s not interesting or heroic in any way. He’s frigid. A sucker fish, seems like a man who never got out alone in nature for a minute in his life. He comes across as a thug or a bully, like in the song . . . “looking for that bully of the town.” He’s not even worthy enough to have a name—comes across as a heartless vamp.

Al Capone is unworthy of folk song because he has no capacity for mercy. But in “My Own Version of You,” the narrator hopes to be “saved” by his creature, if he can “do it upright and put the head on straight.” How’s he going to do that? After all, he’s using parts of that sucker fish Scarface.

Forty-five years ago, Dylan wrote a song that shows how:

By His truth I can be upright

By His strength I do endure

By His power I’ve been lifted

In His love I am secure

He bought me with a price

Freed me from the pit

Full of emptiness and wrath

And the fire that burns in it

I’ve been Saved

By the Blood of the Lamb

We see similar phrasing in a more recent song, addressed to another deity, the “Mother of Muses”:

Put me upright — make me walk straight

Forge my identity from the inside out

You know what I’m talking about

He’ll get the head on straight by putting more Brando in the mix—the “bleedin’ heart” of Terry Malloy. Then the creature might have a chance at redemption, and he might save a few friends too. Here’s Nick Cave again, from “Frogs” on Wild God, taking a Sunday walk with his wife and thinking about that lost child:

Oh Lord. oh lord

The children in the heavens

Jumping for joy

Jumping for love

And opening the sky above

So take that gun out of your hand

We can guess where that gun was aimed.

By some lovely serendipity, or perhaps, grace, today’s New York Times has a moving interview with the novelist Ocean Vuong, in which he recounts an experience he had at fifteen years old, when he wanted to kill someone, but was stopped by what he calls the “satori” of a friend. He tells us that satori is a momentary enlightenment that allows you to alter your life. Vuong’s friend took that gun out of his hand.

Who is this monster, anyway, that Dylan has created?

Does my head look straight? How about yours?

Which brings us to Proof, the subject of Dylan’s other recent Instagram post, who was also a creature of mixed parts. I can’t claim to know the full story, just what I’ve read on Wikipedia, but in the end, in 2006, his inner Scarface gained the upper hand, when Proof killed another man and was killed in a barroom gunfight. He didn’t reach for mercy. No one took that gun out of his hand. Proof sings a lot about death on Searching for Jerry Garcia, the album pictured in Dylan’s post. We are down on the bottom, somewhere near “Key West.” On the cover, Proof tightly hugs the Dead motif, the dancing bones. The rapper apparently admired Garcia because “he just wanted to make fans happy” and so he timed the release of his album to coincide with the ten year anniversary of the guitarist’s fatal heart attack.

Dylan plays us “Kurt Kobain,” the final cut. The song mimics Cobain’s suicide note—although the lyrics are about Proof’s own life—and end with the sound of a gunshot, as Proof whispers “Love killed me.” The Wikipedia page claims this is a nod to the conspiracy theory that Cobain was killed by his wife, Courtney Love, which might have been the rapper’s intention, but we also know that Cobain was killed by his inability to handle the “love” of his fans: Nirvana’s massive popularity. Also his heroin addiction. No one took that gun out of his hand.

Dylan’s post of Proof’s Searching for Jerry Garcia is, like Rough and Rowdy Ways and the other Instagram posts, concerned with the spiritual inspiration of song and its flip side, fandom. Dylan was a great friend of Jerry Garcia’s, and as we know from all the Dead covers he’s performed in concert, also a big fan of his music. On his own record, we hear Dylan’s pledge to devote himself to his audience in “I've Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You.” We hear about his admiration of Jimmy Reed, Jack Kerouac, and all the artists and songs he lists in “Murder Most Foul.” Many other inspirations appear in the lyrics, including Ricky Nelson, Roy Orbison, Mike Seeger, and Elizabeth Cotten. Several of Dylan’s Instagram posts have featured singers and movies he first admired as a teenager in Minnesota. Dylan once said “the highest purpose of art is to inspire,” and as any of his fans will attest, his music has achieved that goal, many times over.

Sometimes, however, those fans can be monsters. Bob’s clip of Proof offers the example of two musicians who broke under the pressures of fame and adulation. Elsewhere on Searching for Jerry Garcia, the pirate philosopher has buried an allusion that both shows the extremity of the danger and offers yet another hidden citation of Dylan’s use of The Golden Bird. Proof’s “72nd and Central” opens with these lines:

Mr Lennon, Mr Lennon!

John, John, could I get your autograph?

Could I get your autograph? (Sure kid)

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, just

Could you sign this for me please (Sure, what’s your name?)

Thanks, thanks, I'm a real big fan, thanks, thanks

(Here you are) Thanks a lot!

(****Screaming****)

Is he alright?

Ay, Somebody call an ambulance! Call an ambulance!

Who did it?

Here we are again, in the penultimate verse of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

I play both sides against the middle

Pickin’ up that pirate radio signal

I heard the news - I heard your last request

Fly around my Pretty Little Miss

I don’t love nobody - gimme a kiss

Down at the bottom - way down in Key West

As I shared in Chapter One, the opening triplet of this verse recounts the experience of a young music fan, a Jesus freak, as he attempts to reconcile his faith with the merciless assassination of his musical hero.

In my last essay, I asked for some help in bringing this story out of the twilight world of “Key West,” into the daylight of commerce and book publishing. I asked if I could get a word maybe, from the man in the shadows, about the truth of my tale. Because the irony is not lost on me, that many Dylan fans, most perhaps, when they hear about a fan thinking he’s communicating with the master on social media, think loony tunes. The irony is that fans can indeed be loony tunes, to a deadly extent. They can be monsters. The irony is that within “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” Dylan includes a preeminent example of this insanity, in a lyric he reimagined from a passage in a fan’s memoir. My own.

And its true, like Bob, I also went a little crazy once, in a different way:

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there

I should have known better than to ask for such superficial help. In this story about inspiration and mercy, all the truth is contained in allegory and imagination, in humor and pun, and of course, in song. In that reality of a more brilliant dimension, Dylan is speaking clearly. All he can do is offer another mirror, another pun, a bit more Proof.

On Searching for Jerry Garcia, the rapper is struggling. He’s on the edge of life and he knows it. He feels the end approaching. He’s on the highway walking toward “Key West.” So on the fifth track, he does what he needs to do. Alone with his ghosts, he confesses. The song is called “Forgive Me”:

Lord forgive me, for I have sinned

Over and over again just to stay on top

I recall memories filled with sin

Over and over again, and again

I appreciate you, my distant friends. May you keep your head on straight in these perilous times. May you find the capacity for joy.

Steven, you might enjoy this article I just finished, which was partially inspired by your post. https://fredbals.medium.com/voices-from-the-grave-bob-dylans-digital-séances-achilles-choice-and-the-art-of-living-63d8be8a8d95

A lot here to like and to think about, but I think you'd find more "Scarface" connections in the original 1932 movie than in the remake.