Welcome back.

As Bob Dylan tours the Midwest and the Mideast, he seems to be taking a break from Instagram. But in late March, he released four posts that I haven’t mentioned so far: an old TV clip featuring Carl Perkins performing “Blue Suede Shoes,” a long audio piece titled “Edgar Allen Poe speaks from the grave,” another audio titled “Stephen Foster speaks from the grave,” and a post with a recording of Paul Robeson singing Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home.” I’m especially fascinated by those messages from the grave—Bob Dylan and AI, sitting around a candle-lit table, holding hands and channeling a couple of his long deceased heroes. Dylan is the great musical medium of the age. As he sang in “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” from Modern Times:

I've been conjuring up all these long dead souls from their crumblin' tombs

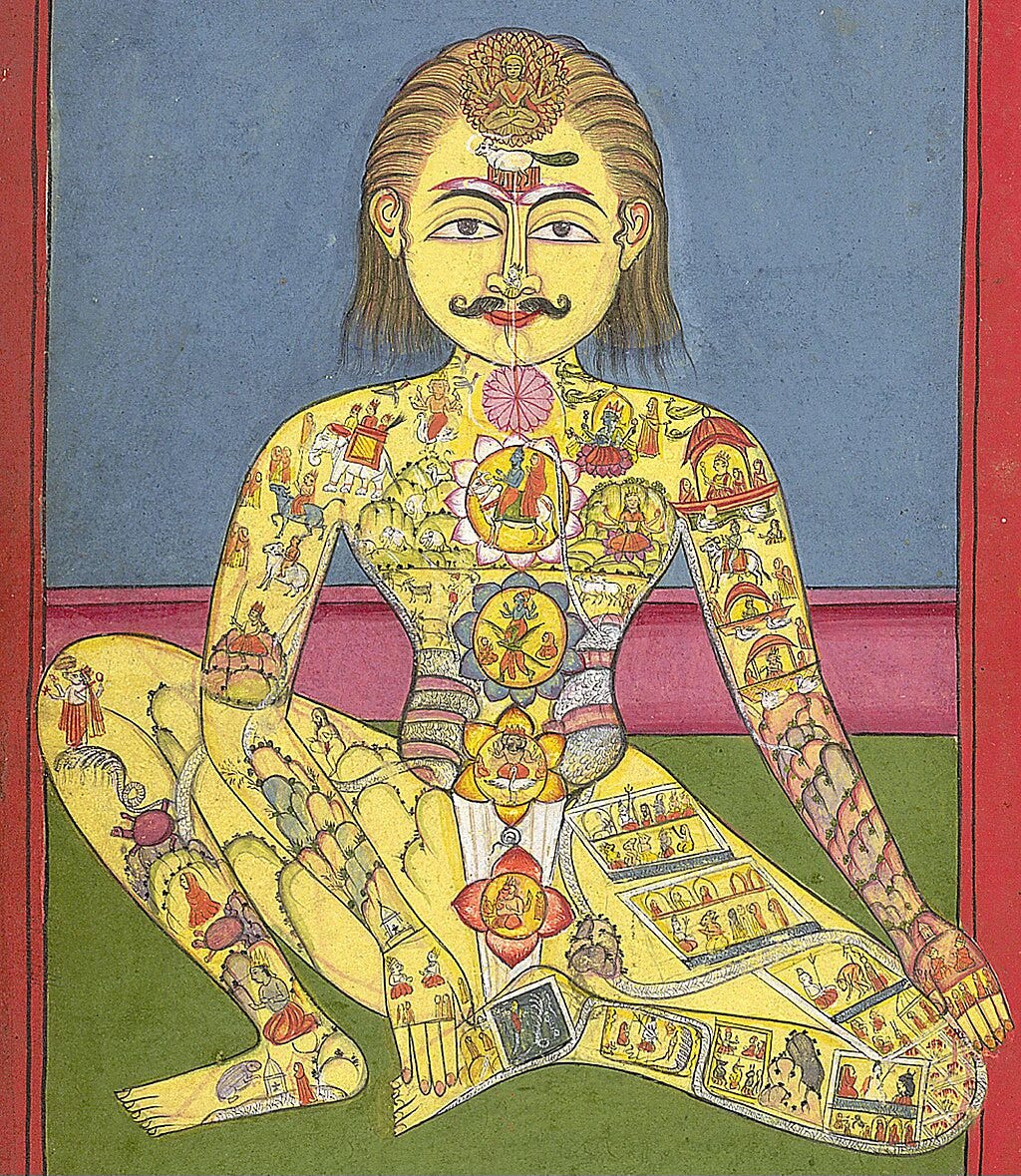

These messages from the other side put me in mind of Dylan’s allusions to Helena Blavatsky and theosophy in Chronicles, and an instance of astral projection transfigured from my memoir into the lyric of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”—an allusion that I’ve reclaimed for the title of this book: “I Don’t Love Nobody.” A key concept of theosophy is that a thin line separates the living and the dead. Another is that we all possess a subtle body, capable of leaving the physical realm and flying free.

As far as I can tell, however, these four Instagram posts are not responses to my writing, so they are not in my purview. I will leave them for others to ponder.

Instead, today I want to discuss Dylan’s disguised citations of his use of The Golden Bird on Twitter and in comments from the stage.

First, however, I have a follow-up to my last piece, about Dylan’s Instagram post of Johnny Cash and the Carter Family singing a lovely gospel about this very day, Good Friday. In that article, I showed that Dylan was mirroring the word “tremble” from “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord” with his own “tremble” at the Hand of Christ, as cited in one of my chapters.

Now recall from Chapter Two, “Bob Dylan’s Pirate Philosophy,” his mention of the Kinks in the 2022 Wall Street Journal interview:

“Waterloo Sunset” is on my playlist and that was recorded in the 60s. “Stealer,” The Free song, that’s been there a while too, along with Leadbelly and the Carter Family.

In that chapter, I told how “Waterloo Sunset” is a song that appears at the very opening of my memoir, as I pass through the London station on my way to Blackbushe. I shared my idea that Dylan juxtaposed the great Kinks tune next to the tedious rocker “Stealer, the Free song,” for reasons other than “Stealer’s” musical quality. I guessed that he was referring to his “thefts” from The Golden Bird.

Only now have I realized that Dylan’s Instagram post of the Carters alludes not only to my citation of his moment of spiritual rebirth, but also to this interview comment, where he first placed the old-time band alongside an allusion to my memoir. The dialogue including The Carter Family began earlier than I’d remembered.

Mirrors and more mirrors.

And as long as we’re back at that very strange interview with Jeff Slate, that reads as if it were written as a spare chapter of the book it was supposed to be about, The Philosophy of Modern Song, I’d like to highlight another of Dylan’s comments. Slate had asked if the technology of recording makes a difference, or if a great song is a great song regardless. Part of Dylan’s response:

It’s bell, book, and candle. Otherworldly. It transports you and you feel like you’re levitating. It’s close to an out of body experience.

Well jeez, I happen to know a great song that features an out of body experience.

Next, those comments from the stage. A couple weeks ago in Wisconsin, Dylan offered a new version of a story he told last fall in Liverpool. After performing “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” he said:

I wrote that at Ernest Hemingway’s house. They let me sleep in it. I got up in the morning and wrote that song. Way down in Key West.

I wonder if he brought a sleeping bag or they if found some of Papa’s old sheets in a closet? Apparently Dylan, while visiting the morgues and monasteries, occasionally sleeps in the museums.

In the essay I wrote about his comment in November, I imagined Bob at Hemingway’s desk, pecking at his typewriter. Now, here in the spring, Dylan puts himself under the covers in Hemingway’s bed, dreaming. He paints a picture of himself waking up and stepping out into the garden, “early one mornin’, way down in Key West”—just like in the version he’s been singing in concert.

When I heard that he’d told this story again, I wondered, could it be physically true? Let’s have a look at the website. I’m not sure exactly where they’re going to put an octogenarian rock star up. I even wrote them an email asking if it was possible, but no one answered. Another crazy person, they thought. Like that old guy who showed up here on a tour and said he was Bob Dylan. He didn’t look anything like Timothée Chalamet.

I wonder if they’d let Timothée Chalamet roll out a futon at the Bob Dylan Center?

Dylan’s story feels like truth, but truth of the folk song kind. I suggest he’s not speaking literally, but rather, speaking about literature. In “Key West,” where the singer walks through the shadows after dark and takes his rest in Hemingway’s bed, he wanders the world of books and song. At Hemingway’s house, Dylan is sleeping and dreaming between sheets filled with Hemingway’s ideas. He’s back in “Snows of Kilamanjaro,” where Harry, while dying, thinks he might be able to put all his neglected stories “into a paragraph if you could get it right.” Dylan, dreaming in Hemingway’s bed, becomes Hemingway. He is another. Papa’s prose is his prose, in Chronicles: “You might be able to put it all into one paragraph or into one verse of a song if you could get it right.”

As I’ve shown, some of the stories Dylan has put into the verses of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” come from The Golden Bird. Why? Because I wrote a book about being a Jesus freak, like Bob. I’m no Hemingway, but I is another.

On to the tweets. At the time, I was reluctant to write about them, because, you know . . . crazy. But the Instagram references have been so direct and explicit in their citation of my writing, so humorous and creative, that I’m newly emboldened to go back to the tweets.

As you know, Dylan issued a stream of them beginning in late September of 2024. His most recent was on March 30, when he offered birthday greetings to Tracy Chapman. Now, March 30 happens to be my birthday as well, and this past one was my 65th, but hey, I can’t explain that. It boggles my mind but I can’t explain it. Sometimes the line between art and magic dissolves.

All of Dylan’s tweets are funny and strange, but as far as I can tell, most have nothing to do with my writing. With many, if there’s subtext, I can’t find it. Who knew Bob would get so excited to meet a Buffalo Sabres player in the elevator? Of course, hockey is pretty big in Minnesota.

Dylan’s first tweet, however, intrigued me:

Happy Birthday Mary Jo! See you in Frankfort.

In the mid-80s, I had a friend in Boulder, Colorado, named Mary Jo. She worked the counter at a sweet little coffee shop I frequented, called Penny Lane (after the Beatles song). She appears very briefly in The Golden Bird, in a scene that features my friend Rich and I talking about an encounter I had with Allen Ginsberg at a poetry workshop at the Naropa Institute, at The Jack Kerouac School for Disembodied Poetics. I excerpted this episode already in Chapter Six, “Hindu Rituals and Gumbo Limbo Spirituals,” but here’s a couple of key sentences:

Ginsberg’s visionary song-poems carried the spirits of Blake and Whitman into the Atomic Age. He would only be superseded by his younger friend Bob Dylan as the preeminent bard of the late century.

Here’s Dylan, hanging out on the freaky side of the railroad tracks, with Ginsberg and Kerouac (and less visibly, their pal Gregory Corso, in my allusion to the “Atomic Age.” One of Corso’s most famous poems was “Bomb.”) Just a few pages later in The Golden Bird comes the “cosmic storm” scene— which gave rise to Dylan’s “Hindu rituals,” as he recently confirmed so poetically on Instagram, via Burt Lancaster.

I’m guessing that Dylan’s shout-out to Mary Jo on Twitter was a shout-out to the scenes she introduces in The Golden Bird.

The next of Dylan’s tweets to catch my eye was his reply, on October 9, to someone with the handle of “VLAD HOSTS THE BEST PODCAST IN BITCOIN.” The exchange is banal, which is a clue in itself. When has Dylan ever been banal? Vlad recommends a restaurant in Prague, the “Indian Jewel,” and Dylan replies:

Sorry, Vlad, got your message too late. The promoter took us out to his favorite restaurant. Next time in Prague though, we’ll definitely be going to the Indian Jewel.

Well gosh, I’m glad they got that figured out. But I suggest that something more than meal planning is going on here. Here’s a section from the “Acknowledgements” page of The Golden Bird:

I am glad each day to walk the Earth in the same time period as Bob Dylan, our greatest American artist and storyteller. “I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours.” Thanks for the invite, Bob.

I’d like to thank Vladimir V. at Third Place Books for his design and publishing expertise. Vladimir is master of the Espresso Book Machine, a technology that eliminates the need for cultural gatekeepers and puts the relationship between authors and readers first.

In isolation, these call-outs to “Mary Jo” and “Vlad” appear random. But added to the wealth of evidence presented in this book, a pattern is unmistakable. And part of that pattern is that nearly every item taken from The Golden Bird for the lyrics of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” occurs alongside a reference to Dylan himself. Here, also, the tweets that I claim cite my memoir arise from passages that include Dylan. And contrary to how it might seem by these excerpts and descriptions, the man doesn’t actually appear in the book very often.

Also, I wonder, at the “Indian Jewel,” do they know all the Hindu rituals?

On November 19, Dylan offered the other tweet that I suspect is associated with my story:

Saw Nick Cave in Paris recently at the Accor Arena and I was really struck by that song Joy where he sings “We’ve all had too much sorrow, now it (sic) the time for joy.” I was thinking to myself, yeah that’s about right.

I hadn’t listened to Nick Cave for years before I saw this and I’d like to thank Bob for the tip. Since then, I’ve played Cave’s last record, Wild God, and the previous one, Ghosteen, dozens of times. They’re brilliant. Readers may be familiar with Cave’s music and his personal history, but for those who are not: in 2015, Cave lost a teenage son in a terrible accident. Both Ghosteen and Wild God have themes tied to that tragedy. Cave speaks extensively about his loss, his music, and his faith in a book of conversations with Seán O’Hagen called Faith, Hope, and Carnage. Cave is a Christian of the humble, non-evangelical, forgiving, repentant, and utterly nonpolitical sort. A real one, in other words. His online “advice” column, The Red Hand Files, is full of hard-gained wisdom. I respect Cave deeply and I’m very excited to see him in concert next month in Portland.

On November 15, four days prior to Dylan’s tweet, I published Chapter Five, “The Bleedin’ Heart Disease,” subtitled, “Finding Mercy with Brando, Down in the Boondocks of Key West.” As you may recall, this chapter discusses Dylan’s allusions to the virtues of mercy and compassion in the lyrics of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” I show how his phrase “the bleedin’ heart disease” originates in the Catholic devotion of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and how several other lines deepen the allusion: the mention of Stephen Mallory, the line about “the convent home,” and a call-out to Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, via “Down in the Boondocks” and “Murder Most Foul.”

All through my chapter, I emphasize how Dylan circles the Christian idea that to find mercy, we must ask for it. We must tell it to the Doctor, if we got something to confess.

In Nick Cave’s “Joy,” a man is in despair:

I woke up this morning with the blues all around my head

I woke up this morning with the blues all around my head

I felt like someone in my family was dead

I jumped up like a rabbit and fell down on my knees

I jumped up like a rabbit and fell down on my knees

I called out all around me, said have mercy on me please

He receives a visitation from the other side:

A ghost in giant sneakers, laughing stars around his head

Who sat down on the narrow bed, this flaming boy

Who sat down on the narrow bed, this flaming boy

Said, we’ve all had too much sorrow, now’s the time for joy

In “I Don’t Love Nobody,” I’ve shown how “Key West” is a place on the horizon line between life and death. In the example of Theosophist L. Frank Baum, as he died, he whispered to his wife that he was ready to “cross the shifting sands.” In my chapter, I told how he wrote an article about astral projection in the Aberdeen newspaper he edited. In Theosophy, the souls of dead children are always close by. In Nick Cave’s interviews, he mentions how he sometimes feels the presence of his dead son. Here’s how he finishes “Joy”:

And all across the world they shout out their angry words

About the end of love, yet the stars stand above the earth

Bright, triumphant metaphors of love

Bright, triumphant metaphors of love

Blinding us all who care to stand and look beyond and care to stand and look beyond above

And I jumped up like a rabbit and fell down to my knees

And I jumped up like a rabbit and fell down to my knees

I called all around me, have mercy on me please

Joy. Joy. Joy. Joy

In the penultimate line, the singer repeats his request for mercy several times.

Can I say for sure that Dylan posted his tweet as a response to my chapter, as a message that I read his allusions well? And to say, speaking of the spiritual power of song, have a listen to this? I don’t know. I do realize it’s pretty weird to believe that the great artist of the age is talking with you on social media. But when I add it all up, the Instagram posts, the other tweets, the long series of connections between “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” and The Golden Bird, coincidence seems like the less rational explanation.

In the end, however, I don’t really care if we stay on the logical side of the railroad tracks. Take me to the freaky side, any day, with the artists. In Dylan’s own words, a great song might transport us and levitate us and take us out of our bodies, to a higher place. “Key West” is not rational:

Key West is the enchanted land

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there

As Nick Cave sings in a song from Ghosteen, “Waiting for You”:

A Jesus freak on the street

Says He is returning

Well, sometimes a little bit of faith

Can go a long, long way

In his tweet about “Joy,” Dylan is expressing once again, “I is another,” this time through Cave’s suffering and prayer and confession and then, in moment of grace, in a visitation from the other side, his joy.

Happy Easter. I’ll leave you with another Cave song from “Wild God”:

I enjoyed reading this tonight, thank you for sharing it. I saw Bob live twice this week and thought of you during Key West. Today, when listening to a bootleg, I wondered what he means when he sings, "Forced me to marry a prostitute" and I thought I bet Steven knows!