Chapter One: The Underground Stories of "Key West (Philosopher Pirate)"

How Bob Dylan Borrowed my Life for His Song

(1) Stay Observant

On June 19th, 2020, Bob Dylan released his thirty-ninth studio album: Rough and Rowdy Ways. I listened to it a lot in that pandemic summer. Dylan’s tour had been cancelled, but the new record held marvels, and with every spin I heard more. I liked all the tracks, but the one that drew me in deeply and my favorite from the start was “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”—a gorgeous meditation, a tropical idyll set at the very gate of heaven.

Dylan admirers first heard of new compositions over social media in March, with this message:

Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years.

This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting.

Stay safe, stay observant, and may God be with you.

Bob Dylan

The linked song, of course, was “Murder Most Foul,” a long Beat-poetic on the Kennedy assassination entwined with a litany of 20th Century musical references. Pandemonium commenced on the blogs and in the discussion forums of the Dylan fan community, as listeners chased down citations and tried to grasp what was happening in the nearly seventeen-minute track. Later in the spring, we heard the welcome news that “Murder Most Foul” was one of ten new compositions to be released in June.

This essay is my answer to the artist’s call to stay observant. Because while listening to the new album in that plague season, I found something that astonished me. I discovered that the lyricist had borrowed imagery from my 2011 self-published memoir, The Golden Bird, in writing one of the songs on Rough and Rowdy Ways. I observed that in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” Dylan had sampled passages from a crucial forty-page section—a series of descriptions of my long-ago involvement in a Christian cult—and remixed them into his lyrics. I realized that the greatest songwriter of the age had transformed my small attempt at art, my reflections on faith, and my very life—strange days I lived as a young man—into his poetry. For nearly four years I’ve been trying to come to grips with this crazy knowledge—trying to understand why Dylan would use the writing of a complete unknown in his composition, and here I’d like to share what I’ve found. My story is about inspiration and mirrors of inspiration down through time. It’s about how live music and music on the radio can change your life. This story, that Bob Dylan gave me to tell you, is about the spiritual power of song.

In “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” Dylan’s dream-like images come alive in the mind as they float along on sunlit waves of Donnie Herron’s accordion. On each lyrical phrase, the other instruments—to my ears, piano, guitar, brushed drums, and stand-up bass—chime together as one. Dylan’s precise, emotive vocal phrasing is both soothing and sorrowful. His whisper of the word “confess” at the end of the third line holds grief and death, comfort and prayer.

I’ve never been to Key West itself, but I passed lot of time in southern Florida as a boy and a young man, so I could easily imagine the song’s setting, “down in the flatlands.” My parents had a condo on the gulf coast during my teenage years, and most of the relevant sections of my memoir take place on the state’s southeastern seaboard, between Daytona and West Palm Beach. Dylan names a few landmarks of Key West and when I looked them up I discovered that most of them are real places. But these lines struck me as odd:

Key West is the gateway key

To innocence and purity

“Innocence and purity” are unlikely descriptors for the real city of Key West. As a moral value, purity has a connotation of sexual chastity. When I imagine Key West, I picture cruise ships, crowds eating ice cream, drunks on barstools, and a fair amount of lascivious behavior. Not “innocence and purity.” Purity is also not a quality I usually associate with Bob Dylan. In the mid-sixties, in “My Back Pages,” the artist famously let go the “crimson flames” tied through his ears by the ideologues of the folk scene. In his lyrics the singer has borrowed from innumerable sources—from Jack London to the punk rocker Henry Rollins—and musically he has used nearly every style known. He’s the craftiest pirate sailing on all the seas and as we all know, pirates are neither innocent nor pure.

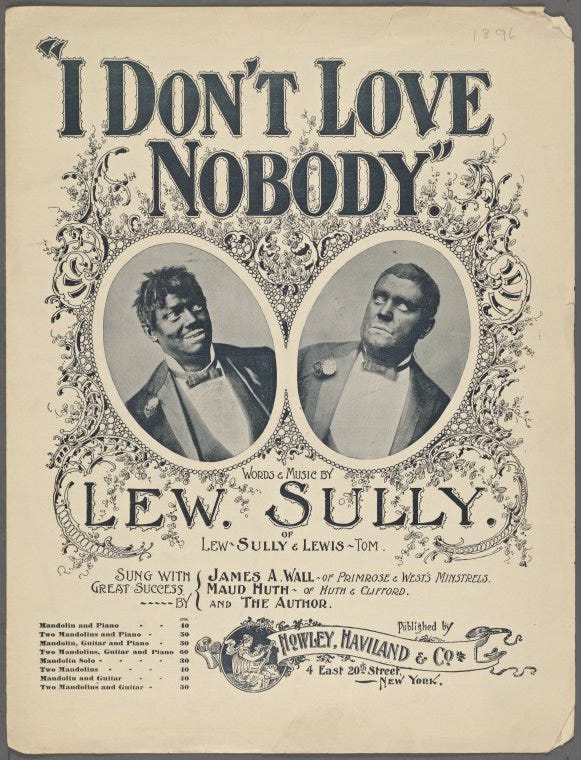

I soon realized that “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is about a lot more than the pleasures of island life. Many of the lyrics seem to be about death. In the opening lines, “death is on the wall” for President McKinley. Key West is “down at the bottom,” “way down,” and “down under.” Dylan also sings about the opposite of death: “immortality." In the second verse, he includes a powerful phrase: “I’m so deep in love I can hardly see.” I couldn’t say why, but I knew this line was about joy rather than mere romance. I recognized the titles of several old-time songs, including “I Don’t Love Nobody”—most well-known in a version by Elizabeth Cotten. In the nineties, Dylan said that old songs are his “lexicon and prayerbook.” Somehow, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is also about going crazy—he uses the phrase “if you lost your mind” in two verses. And he sings about some version of heaven— “paradise divine,” “the enchanted land,” and “the land of light.” Dylan includes a street called “Mystery” that doesn’t exist in Key West—although he says it does, and he even gives directions: “off Mallory Square.” A strange marriage to a prostitute. Toxic plants and bleeding hearts. Hindu rituals and gumbo-limbo spirituals. Pretty obscure stuff, I thought, but it's Dylan. And it’s poetry. That’s what you expect.

But as I played the track on repeat during that long Covid summer, some words and images began to come across as eerily familiar. In the line about innocence and purity, I had a sense Dylan was singing about something that had happened. Another song title, “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss,” had no lyrical context I could find, but the words reminded me of something. I wondered why he would mention an old fiddle tune in a song about Florida. And why did the word “key,” repeated so many times, give me shivers? And more: “under the radar, under the gun.” On one hand, I thought the line was out of place. What did these phrases have to do with anything else in the song? Two clichés together. On the other hand, to me the lyric signified something intimate and sad that I couldn’t quite remember. The phrases were oblique and distant, but I recognized them.

(2) The Golden Bird

In my late forties, fifteen years ago, I was working as a librarian in the Seattle Public Schools. My elementary served immigrant kids who lived in apartments in the surrounding low-rent neighborhood. I loved my job, teaching the children about using libraries, reading stories to the little ones, helping the bigger kids find books, and sharing lessons about literature. I had always liked to write myself—mostly poetry—but I had three children and a job, and I found little time to practice.

When my father died in 2009 at eighty-five, I inherited some money and I was able to cut my hours in the library so that I could begin a writing project I’d had in mind for ages. I wanted to put down the story of my troubled late teens and twenties, when I’d had some crazy adventures, including a year-long stint living on the American highways in a millennialist Christian cult and a near-death experience. I read lots of books on writing, enrolled in a memoir-writing class through the extension program at the University of Washington, and set to work.

I finished my book in 2011 and called it The Golden Bird after a Grimm’s fairy tale. That story uses a folk motif in which a youngest son is able to accomplish a quest where his older brothers have failed. He searches for a golden bird whose every feather is worth an entire kingdom. It’s a story of archetypes—a man goes in search of his destiny. He is foolish and makes mistakes, but because he is willing to accept advice from another world, from a magical helper (a bewitched prince in the form of a fox), he eventually finds the bird and other treasures. In my memoir, I used the bird as my daemon—a shadow aspect of my soul. She is an elemental force within me, a gift of my psyche, both creative and destructive. The magical creature appears rarely but always at moments of danger and turmoil, reflecting my struggles and stopping time.

A second character also passes messages from another world: Bob Dylan. I quote fourteen songs, but the musician appears only in the way that he appeared in my life: in concert, on the turntable, and on my headphones. I mention Dylan infrequently, but here’s the thing: nearly every passage he borrows for “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” contains a reference to his inspiration.

After finishing The Golden Bird, I tried to find an agent, but had no luck. Several friends read the book and said they loved it, but they were friends. I didn’t know if it was any good, really. I was vaguely embarrassed by its intimate disclosures about my past. But I had done my best, and I wanted to see it in print. I investigated a few options for self-publishing and settled on a local print-on-demand service here in Seattle. My wife created a lovely cover, a paper collage of a bird’s wing, and the printer completed the book design. It turned out beautifully. I purchased a box of fifty, distributed copies to a few more friends, and eventually stowed the rest away.

First, however, I mailed one to an office address in New York City. While preparing the manuscript, I had sought rights permissions for the song and literary quotes included in the text. I paid T.S. Eliot’s publishing company to reprint several lines from Four Quartets, and I was granted permission, for a high price, to quote a single Beatles song (“Across the Universe”) in a limited quantity of books. The estate of E.E. Cummings signed off on a few lines from one of his poems. I was denied rights to use a lyric from “Loving Cup” by the Rolling Stones.

I needed permission for the Dylan songs, so I wrote a letter to his publishing company— which at that point was still owned by the artist—listing the exact verses and phrases. I asked if I could reprint them, what it might cost, and I included this synopsis:

THE GOLDEN BIRD is a love story and a quest: the narrator’s true adventures at metaphysical extremes, including, at the core, a ten-month odyssey within a millennial group called the Christ Family. When Steven, an eighteen-year-old Minnesota boy, travels to late-seventies England and attends a rock festival featuring his local hero Bob Dylan, he tumbles into a hole in the earth and cracks his head open. Marie, a married older woman, rescues him, and the two begin an affair that leads to spiritual treasure—represented by the fairy-tale archetype of The Golden Bird—as well as moral and psychological chaos. The inevitable dissolution of their love inspires Steven to seek a life outside of time within an end-of-the-world cult led by Lightning Amen, a man he zealously believes is the reincarnation of Jesus Christ. Steven discards his belongings, including shoes and socks, pulls on a white robe, and for nearly a year walks the highways of America with the brothers and sisters of the Christ Family, sharing ‘the keys to heaven’ with anyone who will listen. After an encounter with his distraught mother, a near-death experience at the hands of escaped mental patients, and an astral violation of the cult’s rule against sex, Steven is catapulted back into society. Over the next several years, in the great woods and farm pastures of the Pacific Northwest, he reconnects to a life in the world, with the help of a young romance, a profligately pot-smoking radical friend, and a Native American professor. The story culminates in the high, thin air of Colorado, where wild nature, unbound sexual energy, and apparitions from Steven’s past collide in a final reckoning. Only after this storm passes is he able to glimpse true faith and understand the lasting gift of The Golden Bird.

Who knows what Dylan’s staff made of that? But a representative replied quickly, saying I could reprint all the songs for free so long as I attributed them correctly.

With a paperback copy of The Golden Bird in hand, I inscribed one for Dylan and sent it off to the same address. I can’t remember what I wrote, probably something like Thanks for all the music, Bob! Hope you like my story! I thought chances were slim to nonexistent that he would receive it. I moved on to the rest of my life: my children, my library work, and my love of gardening. Over the next ten years I also attended Bob Dylan concerts when he was within reach, and sometimes I wrote about them on a blog. By late 2011, I considered The Golden Bird—the story of my young adulthood—history.

As it turns out, I couldn’t leave the past behind. In 2020, a few scenes from my cult days came back to me. My edge-of-life experiences in the Florida flatlands, where I lived for a few months as a wandering ascetic, crazy for Jesus, became lines in an edge-of-life song by Bob Dylan.

How did I figure this out? How did I go from spooky feelings to certain knowledge? It began with those old-time tunes, “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss,” and “I Don’t Love Nobody,” as well as a third song, a jazz standard called “A Kiss to Build a Dream On.” Dylan puts all these together into a single couplet late in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss

I don’t love nobody - gimme a kiss

Sometime during a lazy summer listen, in a flash of recognition, I understood why these lines made my heart twinge. Because I had lived them. I saw that this rhyme, with these song titles, describes precisely a bizarre event I had included in my memoir, late in the cult chapters. Using thirteen words, Dylan transfigures a rapturous moment from the strangest period of my life into song. I’ll tell you about the episode later in this essay, where it will make more sense. The realization knocked me sideways and sent me reeling back to The Golden Bird, where I soon found another half dozen profound connections between my text and Dylan’s lyrics, nearly all contained within the forty page section describing my spiritual conversion.

Now I began to research “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” and the other tracks on Rough and Rowdy Ways in earnest. I discovered that Dylan alludes to dozens of literary, historical, and musical sources carrying the same idea he transposes from my memoir: the spiritual power of song. These allusions are fascinating in their own right, but moreover, they illuminate why the great lyricist would borrow from the work of a fan. They show that “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is a love letter from a fan, from Dylan himself, to the artists he admires. The song is a mirrored room of inspirations.

(3) “White House Blues”

The opening lyric about the assassination of William McKinley at the Temple of Music at the Pan-American Exposition, in Buffalo, New York, in 1901, is a revision of a 1926 recording by Charlie Poole called “White House Blues.”

Poole’s opening lines:

McKinley hollered - McKinley squalled

Doc said “McKinley, I can’t find that ball”

From Buffalo to Washington

Dylan’s version:

McKinley hollered - McKinley squalled

Doctor said McKinley - death is on the wall

Say it to me if you got something to confess

In chapter one of his memoir, Chronicles Volume 1, Dylan recollects that Izzy Young, founder of the Folklore Center, where Bob would hang out in his earliest days in New York City, first played “White House Blues” for him and told him that a band Dylan held in high esteem, the New Lost City Ramblers, had also recorded it. The Ramblers specialized in replications of songs from early in the century; they were pirates of great skill. Later in the same chapter, Dylan writes that Mike Seeger, the multi-instrumentalist of the band, was “the supreme archetype” of a folk musician. He says that Seeger “radiated telepathy” and showed him that live music could be a “spiritual experience.” Dylan writes that he was inspired to compose his own songs after realizing he would never equal Seeger as a traditional player.

Dylan also tells us:

Folk songs were the underground story. If someone were to ask what’s going on, “Mr. Garfield’s been shot down, laid down. Nothing you can do.” That’s what’s going on.

And he finishes the chapter with these words:

I’d come from a long ways off and had started from a long ways down. But now destiny was about to manifest itself. I felt like it was looking right at me and nobody else.

Dylan performs a staggering amount of work with this opening reference to “White House Blues.” First, he signals that “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” with its presidential assassination motif, presents an underground story. He guides us to Chronicles, and specifically to its first chapter—an account of his early glimpses of destiny—as a codebreaker for that story. He conveys, with a simultaneous reference to Charlie Poole and the New Lost City Ramblers, that the tale is about inspiration. He tells us that even the best artists are pirates and that live music is a spiritual force.

In the third line of his revision, Bob buries more treasure. As long-time fans know, Dylan is an avid student of history. McKinley’s biographers, in slightly varying accounts, tell how the president, as he drew close to death, asked for his wife Ida to sit by him, and together they sang his “confession.” The loving couple harmonized on his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” The sacred song, written in 1841 by Sarah Flower Adams, relates the story of Jacob's ladder from the Book of Genesis. It describes how the patriarch falls asleep and sees angels ascending and descending a celestial staircase. The hymn is a prayer; it asks that angels, dreams, sorrows, and song itself may bring the singer closer to God. In the Bible verse, after Jacob wakes, he calls the place the "gate of Heaven.”

“Nearer, My God, to Thee” has significant connections to Dylan’s work. In a 2022 interview, his friend and bandmate T-Bone Burnett explained how “Blowin’ in the Wind” began with the hymn:

In a way, it’s been a hit since the 1840s. This is kind of a rewrite of “No More Auction Block,” which is a beautiful old song from 1865 or so, following the Civil War; it was rewritten at the height of the folk school in the ‘40s as “We Shall Overcome” by Zilphia Horton. But they’re all rewrites of “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” which was written in 1843 or so. You could hang the whole history of the United States from the Civil War to now on [variations on] that one song, between “Nearer, My God, to Thee” and “Blowin’ in the Wind.” I want to say it is a holy song. And every time I’m playing with Bob, I think it’s a holy experience.

And speaking of holy experiences, Dylan name-checked “Nearer, My God, to Thee” in a 1980 gospel-era song, one that takes place in the same tropical setting as “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” “Caribbean Wind”:

The cry of the peacock, flies buzz my head

Ceiling fan broken, there’s a heat in my bed

Street band playing “Nearer My God to Thee”

Folk legend claims “Nearer, My God, to Thee” was played by the ship’s band as the Titanic sank into the North Atlantic in 1911. Many traditional artists have sung versions of the Titanic story, and Dylan recorded "Tempest," his own rendition, in 2012. It tells of men wrestling with their consciences at the time of death.

Let's dig deeper still. McKinley’s killing, as recounted in “White House Blues,” foreshadows two more assassinations. The first, of course, is dramatized in “Murder Most Foul.” And late in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” a single line, “I heard the news,” evokes the tragic death of Dylan’s peer and fellow pirate, John Lennon—as we will see, a reference tightly entwined with Dylan’s use of The Golden Bird.

In his altered lines from “White House Blues,” Dylan gives us layers of allusion, layers of conceptual gold. They describe the spiritual necessity of song, often at a time near death. As McKinley fades away in the embrace of his wife, as Kennedy bleeds out on the way to Parkland hospital, and as thousands on the Titanic meet a tragic fate, the sacred music plays. (In Kennedy’s case, a litany of 20th Century compositions.) Yet in the same reference, the elderly Dylan flashes back to youth and all its creative influences. He flashes back to his gospel period, when he became a Christian. He sings about his own career-long role as a pirate, as a replicator of folk classics. This is the atmosphere Dylan creates in the opening lines of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” We are near the end of days, looking back, living on inspiration and song. We are at the gate of heaven.

(4) Mystery Street

Dylan guides us again to Chronicles in this lyric:

Mystery Street off Mallory Square

Truman had his White House there

As you might guess, because of Junior Parker’s song about a train with the same name, most famously covered by Elvis Presley, “Mystery Street” is a Rock and Roll promenade. But how do we get there? We climb back into Bob Dylan’s time machine.

Our first stop is way back in the 1860s. Mallory Square in Key West is a real place, named for Stephen Mallory, a United States Senator from 1851 until secession, when he was appointed Confederate Secretary of the Navy. In Chronicles, Dylan tells us about visiting the New York Public Library and reading contemporaneous newspaper reports about the Civil War on microfiche. He writes that tragic stories about the War became “the all-encompassing template” to his songwriting. Listeners familiar with songs such as “Blind Willie McTell” and “‘Cross the Green Mountain” know the powerful truth of this statement. In “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” Dylan’s mention of Mallory speaks volumes. The Floridian was a member of one of Key West’s founding families, and, according to his biographer Joseph T. Durkin, he was an adventurer, a philosopher, and a bit of a pirate. As a young man he sailed the Keys, collected recondite literature and idioms for use in conversation, and he eventually married his muse and inspiration, a Spanish-American beauty named Angela Moreno. Mallory was also a devoted Catholic and an original member of St. Mary’s Star of the Sea Basilica in Key West. After the South was defeated in the War, he was imprisoned at Fort Lafayette in the New York harbor. Fearing he might die there, Mallory wrote often to his family, and in one letter included some advice to his son. This quote appears both on the current St. Mary’s Basilica website and in Durkin’s biography:

Cling to your religion, my son, as the anchor of life here and to come. Never permit yourself to question its great truths, or mysteries. Faith must save you or nothing can, and faith implies mystery.

Here we are, on “Mystery Street, off Mallory Square.” But how does this otherworldly “Key West” location concern Dylan’s own fandom of Rock and Roll? Well, first we need to go a little bit Country because, as the singer tells us:

Truman had his White House there

The President had an actual winter residence in Key West, on Front Street, but in Bob Dylan’s metaphysics,“Mystery Street” runs from the flatlands of Florida to the Lake Superior shoreline in Duluth, Minnesota. In 1948, Harry Truman made a campaign stop in Duluth and spoke first from the stage at a building called the Armory. I found this picture of the President being welcomed by the “Duchess of Duluth” in the Minnesota digital archives.

In Chronicles, Dylan writes that his mother brought him, as a seven-year-old, to see Truman address a crowd in Leif Erickson Park, just across the street from the Armory. He writes about the inspiration he experienced:

It was an exhilarating thing, the cheers, the jubilation … Truman was gray hatted, a slight figure, spoke in the same kind of nasal twang and tone like a country singer. I was mesmerized by his slow drawl and sense of seriousness and how people hung on every word he was saying.

In the following years, Dylan often came to the Armory from his home in Hibbing to see musical acts, culminating in a very special show on New Year’s Eve, 1958. Most Dylan fans will pick up this story on their own now. That was the night Buddy Holly came to town on his Winter Dance Party tour, three days before his fatal airplane crash. In his 2016 Nobel Prize speech, Dylan tells us about the show, and says Holly was “mesmerizing.” He claims that the young Texan looked him “right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me chills.”

“Mystery Street” is a place of faith, where destiny waits, where the spiritual power of Rock and Roll can change the course of your life. “Mystery Street” can hold you spellbound.

Other lyrics reinforce the allusions to Stephen Mallory’s faith and Dylan’s biography. In the eleventh verse, the singer claims, “wherever I ramble, wherever I roam, I’m not that far from the convent home.” From 1886 until 1966, the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary lived in Key West at the Convent of St. Mary Immaculate on the grounds of Mallory’s church, St. Mary’s Basilica. And in the eighth verse, Dylan sings about “the bleedin’ heart disease,” a reference to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a Catholic devotion symbolizing Christ’s compassion for humanity. Robert Zimmerman was born at St. Mary’s Hospital in Duluth in 1941, built by the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. They originally lived right next door at the Sacred Heart Institute— another convent home. Bob Dylan has always lived on “Mystery Street.”

Finally, in this place of enchantment, where the needs of the soul are revealed, we come to one more Rock and Roll show, as described in another memoir: The Golden Bird. And like Chronicles, Volume 1, it’s a codebreaker for “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” Here’s a long excerpt from the opening section, called “Blackbushe.” Dylan didn’t borrow anything directly from this section, but I’m including it because it shows how his music had a dramatic spiritual effect on my life. It shows why Bob would use the section that follows for “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”—it’s all about the mirrors. Like the teenage Dylan in the Duluth Armory, my teenage character finds himself on “Mystery Street”:

Marie was a witch. Bob Dylan introduced us.

…

On the fifteenth of July, 1978, a warm and clear morning that tasted of full summer, of cut grass and hot tar, my friends and I began a journey—from my aunt’s home in the London suburb of Leigh-on-Sea to a concert site on the southern downs of Surrey. As we came up from the Tube into Waterloo I hummed a few bars of an old Kink’s hit, “Waterloo Sunset.” I vaguely knew that some old battle had give the station its name, but in my eighteen-year-old mind, rock and roll had made it famous.

On the platforms, a motley assortment of youth waited on trains to Blackbushe. Dapper hippies in paisley waistcoats mingled with shiny rockers in silver boots. Kids with orange Mohawks, clad in torn clothing, safety pins, and zippers, stood in clumps and jeered. The Sex Pistols had assaulted London the previous year with a hit called “God Save the Queen.” I had read about them in Rolling Stone, but I didn’t really understand the punks. In the suburbs of St. Paul, Minnesota, hard rock still meant Led Zeppelin, Foghat, and the Blue Oyster Cult.

…

Around a curve in the road, we came to the festival gates. Once through, my eyes widened to accept the view. Tens and tens of thousands spread over an endless plain. The stage was barely visible—a dot on the far horizon. All these people had come to see Dylan, a young man raised in my own North Country.

Banners had been raised through all the fields, decorated with dragons, or mysterious symbols I would only come to understand later—Yin Yangs, the Om sign—or strange group names like Welsh Bastards for Free Love. It was difficult to move among the legions so we found an open space on the scabby grass and sat. We scalded in the sun. We bathed in the murmur of a hundred thousand conversations.

In the first hours, the music was only an ambient buzz over a human swarm. Large speaker columns scattered through the grounds blasted strong sound but I couldn’t see the musicians. A band called Lake opened with psychedelic metal. In the intense heat, my friends and I sprawled drowsily across our few feet of brown turf. Graham Parker and the Rumor came on next, playing a set of rough white soul.

I barely moved all afternoon. The crowd humbled me and I was afraid of getting lost or crushed. Surges of anxiety passed through me, a sort of claustrophobia, as if I was trapped in a vast pen of swine. Eventually, I went in search of a toilet and returned with a concert t-shirt showing an old red biplane skywriting “The Picnic at Blackbushe” in smoky billows of cursive. My friends wandered away and my nervousness returned. I watched the Asian couple next to me make out.

The scent of marijuana drifted by and I wished I had some. A young British folksinger, Joan Armatrading, came on stage. He clear strong voice chimed across the fields, soothing my jitters. I was away from home for the first time. Despite the company of two boys from my high school, and despite the company of hundreds of thousands of young Britons, I felt alone.

Of course, Dylan would be on stage soon. Two weeks earlier, he had danced through the air in my Midwestern cellar and whispered in the dark about things no provincial teenager could understand. “Isis, oh Isis, you’re a mystical child. What drives me to you is what drives me insane!” What? What drove him? And why did “insane” sound so good?

…

In my parents’ youth, the Spitfires and Hurricanes of the Royal Air Force rose from the tarmac of Blackbushe airfield, defending the island from invasion. More than thirty years later, in a world made safe for rock and roll, Eric Clapton jammed, and finally, as the stars flared above, Dylan took the stage. I was attentive, alert, and calm but, with the band so far away, it was more like listening to a soundtrack from the sky than seeing live music. People swelled and ebbed all around as Bob began to sing:

I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade

Into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way

I promise to go under it

Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me

I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to

The song rang through my head like an incantation.

His large band, with horns, a violin, and several guitars, also played cuts from a dense and difficult new record, Street-Legal. Three Black women sang harmony and response, adding a bizarre religiosity to Dylan’s personal tales. The artist projected strength and confidence, but the words and music suggested a crack-up. Something dangerous was happening. These new songs passed an urgent message in a language I spoke but a dialect I couldn’t quite make out. Maybe Isis—whoever she was—had really driven Dylan insane and insanity wasn’t so great after all. The crowd too had grown crazier through the day, first with heat and then with drink. Dylan’s voice, fierce and triumphant, rode high on the barely contained cacophony of the mob.

“Boooaaaoooobb!!! Booooaaaaaaoooob! Aaaaaaargh!”

Sometimes, now, listening to a bootleg cassette of Blackbushe, I hear that sound—a blurry, distant majesty, thick with promise and dread.

Close to midnight, and before the set was over, my companions and I pulled ourselves up and tottered toward the exit. We were still jet-lagged, needing bed. My uncle had agreed to pick us up in his car at Waterloo station. “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” echoed and faded in the air. We stumbled through the dusty field, past fires and mounds of trash. The road leading to the train had been transfigured by the night into a dark and living tunnel of trees. We siphoned into it and marched shoulder to shoulder with laughing, shouting, chanting Brits.

Then I plunged into the earth. My head hit violently on an edge, something sharp—rock or concrete. I thumped to the bottom of a pit.

I lay for a while in the cool ground, alone in a strange bed, dreaming.

After a few minutes or an hour—I couldn’t tell—I heard voices and roused myself.

I managed to climb up and sit on the precipice. Something warm and wet dripped into my mouth. I dabbed at it with my t-shirt. My high school companion, a boy I barely knew, stood a few feet away waving his hands. The crowd flowed by in slow motion, faces distorted, heads turning toward me and away, bobbing like puppets. The world had become cinematic—an epic scene with a cast of thousands.

I couldn’t will my legs to stand.

A woman appeared at my side. She looked at my head, spoke an oath, and disappeared. In a moment, she sat next to me again and whispered in my ear, “You’ll be alright now. You’ll be alright.”

Had she come from the crowd, or from the breach in the earth?

An ambulance arrived, incredibly, through the congestion. As I was bundled in, my friend yelled some words at me, but I couldn’t make any sense of them. Nothing made any sense. All the molecules that gave shape to things had fragmented. They spun crazily around my bleeding head, rearranging themselves into new patterns.

The woman hesitated for a moment at the door of the vehicle, in the strobe of lights. She looked at me, thinking hard. Was there any choice? She climbed in beside me.

I retched and trembled all along the winding road. The minutes stretched and tore and exploded inside my head until we arrived back at the festival grounds. Inside a first-aid tent, I sat on a folding chair with the other casualties. Judging from the smell of vomit, most of them suffered from too much drink. Eventually, a doctor appeared and while Marie—her name was Marie—held my hand for comfort, he stitched up the two-inch gash in my forehead.

Then the medic set us loose, “Off you go. Be a bit more careful this time, lad!”

Marie protested, “He’s in shock. He has a concussion! He can’t walk anywhere!”

“No, there’s no room, no transport; sorry love.”

We trudged out into the night and found that the concert had ended—the main exodus had begun. I wondered what had happened to my companions. Waves of tired refugees walked the lane to Camberley. I hobbled along weakly, leaning often on my new friend. Several thousand small steps later, we came to a halt in the village, well short of the station, where the crowd had stopped, dead still. A resigned and ragged army filled the high road from one sidewalk to the other. Apparently, the trains had broken down.

Desperate for rest, I dropped to the road and sat in the rustling underbrush of legs and shoes. After a while, Marie pulled me up, held me, and we stood and shuffled through the slow dark hours. Occasionally, I pushed to some nearby bushes, vomited, and staggered back. I felt anxious and claustrophobic again, like a lamb in a feedlot, waiting for the chute open, the gateway to an unfathomable destiny.

A woman appeared at an upper story window, scolding us. “Shut it, you noisy buggers!” She came again later and threw a bucket of water on us. Another lady, in curlers and gown, toasted us with a cup of tea.

Through the night, Marie smiled and propped me up.

Finally, at first light we moved forward. As Marie and I gained seats on a train to Waterloo, she said, “You’ll remember this, eh? You’ll see this night on your head for a long time to come.”

Thirty years on and a scar still lines my brow, faint but visible. It’s a reminder of a song and a dancing spell. It’s the mark of a black night, an opening in the earth, and a blind fall. I spilled blood in the soil of England. Something hidden shivered and woke.

I went to the festival called Blackbushe to see Bob Dylan, and I found something else, “something I didn’t know what.” Marie was nine years older than I, a half-pagan, half-Catholic beauty from the island of Guernsey. She taught me sex and gave me a glimpse of the divine. She was, without a doubt, a character out of a Bob Dylan song.

(5) Jesus

Near the end of this 1978 world tour, I saw Dylan perform again in Portland, Oregon, where I had just begun my first semester at college. I also describe this show in The Golden Bird. Two weeks after that show, Dylan had a vision of Jesus in an Arizona hotel room. His next three albums and his 1979 and spring 1980 concerts featured exclusively newly written gospel songs. This change of direction plunged the songwriter into conflict with his audience, his critics, and eventually his record company. Some fans were appreciative, but others heckled him in a replay of the time after Dylan had gone electric and alienated folk purists. In recent years, and especially since the release of a comprehensive overview of the songs in a 2010 “Bootleg Series” release called Trouble No More, many listeners have recognized that Dylan’s creativity during this period, especially in the live shows, was at a peak. The singing is extraordinarily expressive and the bands he assembled rocked hard. There’s no denying, however, that the songwriter had walked out on a thin edge. During this time, he often preached from the stage, and he seemed to believe that the End was nigh. Here’s what he said in Maine on May 9, 1980. His rap contains a phrase that will appear forty years later in the chorus of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” You’ll see it:

… you need the power of God in you. Power of God manifested in the flesh, justified in the spirit, preached out in the world, believed on in the nations. Raised on up into glory. You need that kind of power. Or you ain’t gonna make it. You’ll die all right. You’ll live and you’ll die. I know you might look at me and say, “Wow, he’s just lost his mind!” But I never did lie to you … I’m telling you the truth now but it’s like trying to tell somebody what a piece of bread tastes like …

I first heard Slow Train Coming in the fall of 1979; my affair with Marie had come to a brutal end and I was hanging around the London squat of a friend, waiting, of all things, on Marie to give birth to her first child. Not mine. Here’s how I put it in The Golden Bird:

I went to London to consider the next move. I wasn’t ready to return to America. Nothing waited there but the uncertainties of college life. I wasn’t done here, not yet. Marie’s baby was due in November.

So I hung around Theresa’s flat again, listening to records and eating her parsnip soup. The LP I listened to over and over was the new Bob Dylan, Slow Train Coming. It grabbed me. It was Christian, with no masks. Dylan had always had a spiritual influence in his songs, but never so plainly, so gospel. I lay across Theresa’s bed while she was at work, contemplating where I had gone wrong:

Change my way of thinking

Make myself a different set of rules

Change my way of thinking

Stop being influenced by fools

I knew a fool, right inside of me. A year before, in Portland, the singer had seemed close to madness. On this record, after a bad stretch in his life he was spelling out his beliefs. Now I was the one floundering and making poor choices. Bob was saying look to the teachings of Jesus.

Do you ever wonder, just what God requires?

You think he’s just an errand boy to satisfy your wandering desires

When you gonna wake up, when you gonna wake up

When you gonna wake up and strengthen the things that remain?

Listening to these new Dylan songs, staring out my friend’s window at a little black girl kicking a ball and swinging her beaded braids, I caught a flash of wings and golden light. Maybe if I shook myself hard enough I could wake up.

(6) John Lennon

In a moment I’ll describe how my plunge into End-of-Days Christianity, shortly after the scene above, is the direct reflection the lyricist takes from The Golden Bird and recasts into “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” First, however, let’s consider Dylan’s great frenemy and only true peer, John Lennon, who is also highlighted in my memoir and mirrored in Dylan’s song. From Part One of The Golden Bird, on the morning after I first sleep with Marie:

… I turned on the radio by the bed and the first song that played was the Beatles—John singing “Across the Universe” like it was still 1969. Sunlight shone through the windows—a bright clear day … Living was a natural ecstasy … A hanging prism cast refractions on every wall and on Marie’s brown body curled beside me.

“nothing’s gonna change my world”

In “Key West,” we catch a glimpse of Lennon in the second verse, in the reference to Radio Luxembourg. Teenage John often listened to the “pirate” station, to Little Richard and other early Rock and Blues, in his childhood bedroom at Mendips:

I’m searchin’ for love and inspiration

On that pirate radio station

It’s comin’ out of Luxembourg and Budapest

All of the beauty and sadness in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is broadcast over the radio. Dylan’s city of “Key West” is, in itself, a song, so even nature—the flowers and the wind—comes to us over the airwaves, as the real thing, but also more than the real thing, as in a hymn, elevated.

Here’s the opening paragraphs of the section of my book titled “Lightning Amen”—the discrete forty pages from which Bob Dylan took imagery—with another reference to Lennon:

In late May of 1980, I completed the second quarter of my sophomore year at the University of Oregon. I had no academic direction. College was only a place to be, where I didn’t need to worry about working and where I could chase my only ambitions: romance and an elusive ecstatic ideal.

All winter, I’d lived in a tiny lofted bedroom in a shared rental on one of Eugene’s busiest arterials. The house stood smack in the center of a parking lot. Each morning, I left for classes, squeezing between the cars of students, professors and office workers. In the late afternoon, I’d walk home, put The White Album on the turntable and two pots on the stove. While lentils and rice bubbled, John and I screamed about our loneliness in “Yer Blues.” After dinner, I’d scrub the pan to the Rolling Stone’s “Loving Cup,” and dream up a girl who might want to push and pull with me all night. I was hungry for anything that offered a beautiful buzz.

(7) Losing your mind

Two pages later, we find the first image—a near exact phrase—that Dylan borrows from The Golden Bird. Or more accurately stated, in this story of mirrors, we find an image that Dylan borrows back:

I’d been reading spiritual texts of different kinds, mostly Zen and other Buddhist tracts, with a little of the Christian mystics thrown in. Their descriptions of an enlightened state matched my own brief periods of transcendence. I wasn’t disciplined enough, however, to devote myself to the required meditation of the Buddhists or the solitary self-denials of the Christians. I was too full of energy and desire.

I wasn’t even listening to Dylan anymore, not his new stuff anyway. He’d followed Slow Train Coming with another Christian album, called Saved. In England the previous October, while hanging around at Theresa’s, I’d been impressed by Dylan’s new convictions. They had given me hope at a moment when hope seemed futile. Now, back in the vast New World, I’d been influenced by my college buddies. They thought Dylan had lost his mind, trading creative thought for the dictates and dogma of a narrow creed. My friends disparaged these records as uncool and impossible to relate to. Logically, I also couldn’t see how the artist’s focus on Jesus, on one single religion, could lead to any higher awareness.

My phrase concerning the perception of my “college buddies” toward Dylan’s new music (or is it Dylan’s phrase concerning the perception of his college crowd?) finds a new home in the chorus of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

Key West is fine and fair

If you lost your mind you’ll find it there

Key West is on the horizon line

The following paragraph includes yet another reference to Lennon:

I listened to other titles in my collection instead. When I wasn’t in class or in a bookstore, I spent my time in record shops flipping through the racks of vinyl. I owned many classics of the sixties and seventies: the Byrds, Cream, and all of Lennon’s solo albums. Most often, I felt closer to these musicians through their work than I did to any real live humans.

As Dylan exclaimed in his gospel rap and as I reflect in the passage above, when the singer became a Christian most hip people thought he had gone nuts. Many fans put him aside, as I did, in favor of cooler artists, like Lennon. But here’s the thing: two pages later I also lose my mind. I meet Jesus in a university bathroom. Or a cult version of Jesus, but it was all the same to me:

I could only articulate the obvious. “You’re Jesus.”

He smiled. “I have something to tell you. Will you come outside?”

I followed him, and it occurred to me I had died. Nothing else made sense. There must have been an accident. Something had killed me, fast, and it hadn’t hurt at all. My body, gleaming and immaterial, wasn’t my body at all. It was something different, something changed.

Soon I am sitting in a converted school bus, surrounded by men and women in white robes, and I hear about “the keys to heaven”: No killing, no sex, no materialism. I accept these tenets as if I’d always known them:

In a single moment, my brief life had been rendered, strained of impurities, and recast in a new form. Christ had come as promised in stories from childhood: “like a thief in the night.”

From “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

Key West is the gateway key

To innocence and purity

Just after my conversion, I am with the cult members at my student rental house, disposing of my possessions so that I might join them on the highways:

We filled trash bags with the contents of my room. I threw in the Blackbushe t-shirt that had once sopped the blood from my cracked head. I threw in my Guernsey sweater.

Micah said, “Your glasses, too.”

“But I can’t see without them.”

“You can, brother. You have new eyes.”

I tossed them into the sack.

And a couple pages later:

In the morning, I felt just as high as I had the night before. The Christ Family was my own. I was in love and, for the first time since childhood, my love held no ambiguities. I had done the only possible thing.

Earlier, I showed how the first verse of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is about the spiritual power of song, about inspiration and destiny, about death and the need to confess, as evidenced by “White House Blues.” In the second verse, the narrator suddenly encounters the deeper source of that feeling:

I’m searchin’ for love and inspiration

On that pirate radio station

It’s comin’ out of Luxembourg and Budapest

Radio signal clear as can be

I’m so deep in love I can hardly see

Down in the flatlands - way down in Key West

The startling leap between the two triplets reflects a spiritual rebirth. The “radio signal” has become a holy vision and the narrator is suddenly “so deep in love I can hardly see.” This, by the way, is my favorite lyric of the song. Dylan, while expressing a deeply mystical feeling, also manages to pun the disposal of my glasses into the line.

But hey, thinking about cults, isn’t it likely that I was mentally ill and these people took away my glasses to control me? It's a good question. It’s a rational question. And it’s beside the point, or looked at from another angle, precisely the point, because:

If you lost your mind you’ll find it there

Nothing about a visitation from God is rational. Recall the other item I tossed into that trash bag: my Blackbushe t-shirt. At this moment, in the spring of 1980, Bob Dylan was on the second leg of his gospel tour, where he declined to play a single number from a catalog that had changed the nature of popular song. He had tossed all his hits into the trash for Jesus. Not only that, he was preaching that the Russians and the Chinese were about to go at it on the plains of Armageddon.

I’ll give you crazy.

“Wow, he’s just lost his mind!”

He was also performing some of the most beautiful and powerful music of his career. He didn’t care what the money men at his record label said. He was so deep in love he could hardly see. This, I believe, is why Bob Dylan would borrow my imagery for his song: He came across a mirror, not only of a fan inspired by the artists he admires, not only of a fan with a head broken open by the mystery of live music, but of a fan willing to abandon “Bob Dylan” for a higher love. A fan who had also “lost his mind” for Jesus.

(8) Down under in the Keys

The “keys to heaven” were the foundational understandings of the cult, the values that held us together. First came an ecstatic moment: a vision of Christ alive in the world, but out on the road, walking the highways of America, we were all about “the keys.” To anyone who would listen: “the keys”: Total veganism, celibacy, and a surrender of all possessions, except for a white robe, a blanket, and a toothbrush. I’m not sure where these behaviors might rank in 2024 on anyone’s list of trying to do right in this complex and corrupt world, but you gotta admit, they are virtues. A person can’t live on earth like that, however, unless you’re some kind of crazy monk.

We were some kind of crazy monks, walking the highways of America in our bare feet. Except we called it “in the wind.”

Feel the sunlight on your skin

And the healing virtues of the wind

By far, the word that repeats most in Dylan’s song is “key.” It appears in every verse at least once, in several verses three times, and in a couple more, four times. And as we know, this tune is not about the real city of Key West:

Key West is the gateway key

To innocence and purity

(9) Truly Blessed

About seven months and twenty pages later, in December of 1980, I was staying in one-story, three-room farmhouse in a rural area near Indianapolis with two other members of the Christ Family. I had been ecstatic for my entire half-year in the cult, but in the deep winter of Indiana, a measure of doubt had seeped in. I wanted to get to Florida—where I’d been told the Family roamed and gathered in cold season—to be living outdoors, preaching “the keys” on the street and telling people that Christ was back. But for now I was stuck in Indiana with a “brother” and a “sister” whom I didn’t quite trust. I began, for the first time in months, to reminisce about the family I had abandoned, and Marie, my only lover. Then, on a grey winter afternoon, a report coming across the airwaves throws me into crisis:

Struggle as I might, I can’t come up with how I hooked up with Jack and Rose, but I remember precisely when I heard the news on the radio. It was December 9, 1980. We were driving back to the hideout in a van with a faulty heater, from some errand in Indianapolis. We’d been chugging along for ages, past strip malls and cold, dead cornstalks and the stench of pigpens, through the flat fields that stretch forever in rural Indiana.

John Lennon had been shot by a crazy man, outside his apartment in New York City.

Jack said, “Ha, it’s part of the plan—another false idol gone.”

Rose said, “Amen.”

I was shocked—by the news and their reaction. I had loved and admired John. John believed in love …

Jack pushed a cassette into the player, a recording made at the Christ Family camp in Arizona. I usually found pleasure in these songs, but now I wished the brother had left the radio on so I could hear more about Lennon. Instead, the clear voices of the sisters’ choir filled the frigid air. I couldn’t find the words very comforting:

“Everything’s a blessing. So count your blessings.”

Lennon’s death hit hard, even for a young man who thought he’d abandoned everything in the normal world. So I’m not very receptive when the brother puts that cassette in the player, and as Dylan sings, in the ninth verse of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

People tell me that I’m truly blessed

(10) Both sides against the middle

I begin pondering the strange path that I’m on:

That evening, I crept out of the house, started the van, and tuned into memorial shows on FM radio. The song “#9 Dream” reminded me of childhood. I thought of the warm sun in my St. Paul backyard and my sister’s arms surrounding me. That time didn’t seem real. Was it just a dream? I also remembered, across a great distance, Marie, and a summer morning in Battersea. In that perfect moment, John’s voice had spoken to me on the radio in “Across the Universe.” I though I had found a love that can never die.

Now the DJ played the song “God.” This one confused me. The lyrics equated the idea of God with personal pain. Lennon lists all the icons and concepts he’s discarded: Elvis, Jesus, Zimmerman, and even the Beatles. He just believes in himself and Yoko. I considered how John Lennon and Bob Dylan had inspired me to think outside the confines of my own upbringing. They had led me to Blackbushe, to Marie, and to a mind-altering shock of ecstasy. They had led me to a revolution of my soul.

When I joined the Christ Family, I had abandoned their music with everything else. Now, for the first time in months I listened again, and Lennon sang that even God was just a box. He was a box the size of your own despair. Here in the cornfields of Indiana, on a bitter December evening, I could nearly see that. I could nearly imagine alternatives to this life I had chosen. I could nearly imagine other possibilities of what might be true.

Once again, the radio is where all the action happens in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” As the DJ spins songs by the ex-Beatle, I have an argument in my head. I sit, a crazy Jesus freak, in a cold van in Indiana, in my white robe, and, as Bob Dylan puts it in the opening triplet of the song’s penultimate verse:

I play both sides against the middle

Tryin’ to pick up that pirate radio signal

I heard the news - I heard your last request

Dylan recasts my dilemma into his lyric. I play my invisible belief in Jesus against the brilliant inspiration of Lennon. God on one side of the dial, “God” on the other. Where is the advantage? These lines reprise and update the second stanza, when the radio signal was “clear as can be.” Now, in the wake of Lennon’s death, I’m encountering lots of distortion. Because I heard the news. Where does a fan turn when inspiration itself has been assassinated? What’s a zealot to do when God leaves you in a cold box? I wonder if my faith is an illusion. A concept by which we measure our pain.

We can be sure the third line refers to the pirate John Lennon—who borrowed everything he could from early rockers like Little Richard—because Dylan also uses “I heard the news” in his 2012 tribute, “Roll on John.” This line is in turn a play on Lennon’s own “I read the news today, oh boy,” from “A Day in the Life.” And it is the phrase I use in The Golden Bird when I learn about his murder. Lennon has been with us here in “Key West” all the while, but only now, in the thirteenth verse, does he show his (ghostly) face.

(11) False Prophets

Once again, Dylan creates his poetry from a passage of my memoir in which he appears. And significantly, the artist uses an episode in which his mythic status, and John’s, is called into question. I hold up Dylan as an inspiration and Lennon’s song takes him down, along with Jesus and the Beatles, as unnecessary objects of worship. I hold up Lennon as an inspiration and Jack calls him a “false idol.” Fans will be reminded of “False Prophet,” another song title on Rough and Rowdy Ways. On that track, and here just below the surface, Dylan reflects Lennon’s theme in “God.” He considers the iconic role of our musical heroes. After they’ve changed our lives, can we allow them to be just humans, just artists? The evidence suggests we cannot. Sometimes, in fact, we kill them. And the musicians themselves, as much as they’d sometimes like to escape the spotlight, are ultimately unable to deny their role as cultural seers. In “God,” Lennon only manages to reinforce his power as a spokesman for the iconoclast. Similarly, in “False Prophet,” Dylan is all ambiguity as he claims, using a triple negative, “I ain’t no false prophet - I just said what I said.”

(12) Last Requests

In “Murder Most Foul,” Dylan asks Wolfman Jack to play us a series of 20th Century songs as a benediction over the body of a dying president. The Wolfman is soothing us with songs on that pirate radio. Here, in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” just underground, down on the bottom, we hear another litany, a litany of Lennon.

Play it for me, Wolfman, play me a last request: “God.”

Play “#9 Dream.”

Play “Across the Universe.”

Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is a story about the meeting place of the material world and the spirit world. It’s a hymn that offers John Lennon’s songs—buried like treasure, buried as a whisper of grief in a single line—as another kind of gospel. Lennon was anti-religion, but in the songs, his spirit lives on. For any child of the late 20th Century, as for Bob Dylan, they are part of the “lexicon and prayerbook.”

The only advantage is found in the songs.

I have doubts about my path, but I stay with the cult. Or, as Dylan sings in the fourth verse:

It may not be the thing to do

But I’m stickin’ with you through and through

Play it for me, Wolfman, play me a last request: Play “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”

(13) Fly around

From the end of this episode in The Golden Bird:

Each night after dinner, we lay smoking and staring into the dark. I began to have lucid dreams. I knew I was dreaming and I could fly. I didn’t actually go anywhere or do anything. I just practiced take-offs and landings. I began to look forward to sleep. Maybe I was undergoing some kind of initiation, a new stage of development. By day, I was a monk in a chill cell, a prisoner of God. By night, I was again finding freedom.

A month or so, and seven pages later, I am walking the Florida highway with a sister I call Rebecca. With two other Christ Family members, whom I have recently met by the side of the road, we have converted her and two friends:

They turned on exactly as I had, back at the university in Eugene. It wasn’t the keys alone, or anything else Gary said. It was an ecstatic release—a letting go of the disappointments, the broken promises, and the complications of adulthood.

We found some sheets, sewed up robes and carted all their stuff down to the dumpster. We slept on the floor, six people thinking as one, happy as only children can be. The next day we walked south down the highway.

Key West is the place to be

If you’re looking for immortality

Stay on the road - follow the highway sign

Key West is the gateway key

To innocence and purity

Key West - Key West is the enchanted land

(14) my Pretty Little Miss

The “keys” and the force of our belief took us daily to another world. But now something had changed. I had fallen for Rebecca:

In the late afternoon, I led Tony and Rebecca into a patch of woods by the side of the road. We stepped over dead palm fronds and eucalyptus roots and weaved our way to a small secluded clearing, away from the sounds of the highway. We cleaned empty bottles from the ground and pulled a few plastic bags from the trees.

I gathered sticks for a fire while the others rested their feet and rolled cigarettes. The sky darkened and my newly kindled blaze lit Rebecca’s face. She’d been working at a strip club but seemed innocent by nature. She couldn’t be any older than my twenty. I could see myself in her.

We heated our beans and fed them to each other out of the pan. Then we lay in our sleeping bags, smoking and contemplating the sky. Rebecca was in the middle.

I fell to sleep, but in the next moment I was strangely wide awake. Rebecca and I lay together in some other glade, like the one that held our bodies but radiant, with a light stronger than the moon and softer than the sun. It wasn’t Florida.

Our robes disappeared and we made love. Our bodies felt lighter and more acrobatic than the ones we’d left behind on the dirt. I touched her face and lips and it was a physical sensation. We were inside of each other. Rebecca came into me as much as I came into her.

In the morning, our eyes opened at the same moment.

“I had such a dream, Steven. Was it a dream?”

The second triplet of the “playing both sides against the middle” verse, with its precise description of the passage above translated into the language of song, provided my initial recognition that Dylan had borrowed from my book:

Fly around my Pretty Little Miss

I don’t love nobody - gimme a kiss

Down at the bottom - way down in Key West

“Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss” is an old fiddle tune about wanting to marry a girl, about chasing her through the air, up around the cherry tree, where she’s “bound to drive me crazy.” Here, Dylan puns again on my text: I don’t love no “body.” The lyrics of Rough and Rowdy Ways contain many such references to the supremacy of spirit. In “False Prophet,” for example, Dylan sings:

Can’t remember when I was born and I forgot when I died

Here is Lord Krishna to Prince Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita:

He is never born, nor does he ever die; nor once having been, does he cease to be. Unborn, eternal, everlasting, ancient, he is not slain when the body is slain.

In the same song he claims:

I ain’t no false prophet - I’m nobody’s bride

Again, we hear about a mystic marriage to no “body.”

(15) Mirrors and kisses

Another story behind the allusion is less ethereal. “I Don’t Love Nobody” is a racist song written in 1896 by the black-face minstrel Lew Sully. In 1956 it was repossessed by Elizabeth Cotten, a Black woman of great soul. When Cotten recorded Sully’s “I Don’t Love Nobody,” she walked through a rusty old mirror and made something ugly into something beautiful and holy. And remember Mike Seeger, Bob’s inspiration for performance as a “spiritual” force? He ran the tape machine for “I Don’t Love Nobody” and the rest of the album on which it appears, Folk Songs and Instrumentals with Guitar. The LP became an inspiration for many musicians, including a young Jerry Garcia and John Lennon of the Quarrymen. “I Don’t Love Nobody” is a song of redemption. And in its double negative we find another mirror: Love everybody.

The Philosopher Pirate, to John Pareles of the New York Times in 1997:

You can find all my philosophy in those old songs. I believe in a God of time and space, but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs. I believe in Hank Williams singing “I Saw the Light.” I’ve seen the light too.

“A Kiss to Build a Dream On” is an old song, a 1935 tune by Bert Kalmar, Harry Ruby, and Oscar Hammerstein, recorded by many artists, including Louis Armstrong and Bing Crosby:

Give me a kiss before you leave me

And my imagination will feed my hungry heart

Leave me one thing before we part

A kiss to build a dream on

(16) Under the gun

Of course, I didn’t know Rebecca was about to leave me. But sex, even the dreaming kind, was not allowed in our merry little band of Jesus lunatics. The next day, and a couple pages later, other members of the cult catch on to our romance and we are separated. My doubts again overtake me, and I climb into the wrong car:

The driver screeched off as soon as I closed the door. He turned to me and I found myself looking at a bulgy, square head, slit by a vicious smile.

He said, “Why, don’t you boys look pretty in those dresses? I know what a boy in a dress likes.”

A fat, pale, greasy-skinned woman sat in the middle. She smacked her fake pink lips as she spoke.

“You boys—you are boys, ain’t you?—you just made a stupid mistake!”

I didn’t understand these people. Most folks who picked us up wanted to ask questions like why we dressed in robes and walked on the road. These ones were just mocking us.

“Jesus is back, ma’am.”

This cracked them up. An especially loud cackle issued from the back seat.

“Well, fuck me!”

I turned my head to see a young man’s lean acne-scarred face and an open mouth filled with rotten teeth. But my attention was pulled quickly to a long blade shining in the boy’s fist and its position against Tony’s throat. The brother’s eyes were wide in panic and fear.

“We’re peaceful people. Please let my brother go.”

The knife wielder flew into a rage.

“You fuck! I’ll carve his neck open! See if your fucking Jesus cares! Shut the fuck up!”

I lost courage and kept quiet. The woman spoke.

“Best not to rile Thomas! He’s kind of touchy. I’m a lot sweeter. Look at me boy! Ain’t I pretty? And look what I got down here between my legs!”

I hesitated, closing my eyes and praying hard.

She screamed in my ear, “Look between my legs you little fucker! You gay or something? Look!”

I did as I was told and saw something even worse than I’d expected. A small handgun was tucked between her thighs. She began to stroke and caress it with both pudgy hands.

“Oh I like it. I like it here. Do you want to feel it?”

My face was tight. I could smell my sweat. She lifted the gun and held it to my head.

“Pop! Pop! Pop! Ha, ha, you silly boy! I’m not going to shoot you. Not yet anyway.”

She tucked the gun back into its special place.

Dylan, in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

Key West is under the sun

Under the radar - under the gun

My time with the cult was coming to an end. I survived that day in the Florida flatlands, but my entire ten months in the group was a near-death experience. The Christ Family was a truly bizarre cult. From down on the bottom and out on the highway, we had no reference points in the world. We could not be found by the families and friends we had abandoned, and we did not want to be found. We believed we were dead to the world. We believed that we lived in a place on the borderlands of Heaven. We were under the Son and absolutely “under the radar” too.

I invite you to read about my crazy youth and cult days in The Golden Bird. There’s a lot more to the story than what I’ve shared here, and as well as I can figure out, Bob Dylan seemed to like it. I think he saw some mirrors, and although my mind boggles to say it, I think he found some inspiration. Obviously, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” contains many lyrics I haven’t discussed here, including an odd reference to a prostitute. I’ve got ideas about all of these lines, but as most are not clearly entwined with Dylan’s use of my memoir, I will leave them for another day.

(17) You’ll find it there

A few pages after the incident of the gun, I end up in jail. Another three pages and a couple months later, I am back in Oregon, trying to figure out how to live again in the “real” world. I place a bookend on my cult experience with a variation of a phrase I used forty pages earlier:

I returned to Eugene. My old college friends looked at me with pity. They thought I’d lost my mind and I couldn’t blame them. All of them took pride in counter-cultural credentials, but I had pushed the limits. I was a bad freak among good freaks. I moved in with an orthodox Jewish man who wanted help in his garden.

In the final verse of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” Dylan places a bookend on his borrowing from The Golden Bird:

Key West is fine and fair

If you lost your mind you’ll find it there

Key West is on the horizon line

I appreciate you reading my story, friend. It’s still blowing my mind every day. I feel like I’ve got this obligation to Bob to put it out there. Comments like yours help me believe I’m doing okay. Thanks man. Long live Bob Dylan

Well, this is a sweeping, fascinating essay. Thank you for this. What a vivid and moving connection.

What you suggest here about Dylan's creativity - his particular way of absorbing pellets of ideas and imagery and recombining them into songs - and about his spiritual experience of song is resonant with my own sense of his work. The most significant artist of my own life, by far.