Bob Dylan's Instagram Posts Part 4

The Hidden Story

Author’s Note: This essay was nearly complete when Bob Dylan added three new posts to Instagram, on February 26. Here, I only discuss the clips from February 16. I can’t say yet whether the new posts continue the story I tell below, or whether Bob is off on some other track. More about those later!

Welcome back. I’m glad you’re here.

More than four years ago, I realized that Bob Dylan had used the narrative of my 2011 memoir, The Golden Bird, in composing much of the imagery for his song, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” My mind was blown. Since then, I’ve felt a calling to figure out why, and to tell the story. I’ve put hundreds of hours into research and writing, and the result, after many drafts, is my nearly completed book, “I Don’t Love Nobody”: Hidden Stories from Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways. Over the past couple years I’ve been publishing my revisions here.

Recently, there’s been a new development. I’m smiling a lot lately, because on Instagram, Bob Dylan is speaking about my work. His posts over the past few weeks are a response to my chapters. The evidence is overwhelming.

Dylan is speaking in the way he often does, subversively and indirectly, with the voices of other artists and characters, the voices he inhabits with such genius. He is speaking with allusion and humor and pun and the spiritual inspiration of song—which is what this story is all about. He is speaking with the same artistic technique he employed to transfigure prose from The Golden Bird into the poetry of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” On Instagram, Dylan is speaking with mirrors.

On February 13, I published a piece on Dylan’s second series of Instagram posts, which I concluded with an invitation for his feedback. On February 16, Dylan published an answer: three more videos.

You’ll want to read “I Don’t Love Nobody” from the beginning, as well as my earlier writing about the first eleven Instagram clips, for the full picture.

Let’s look at the most recent posts. The first is a studio segment of Lowell George and Little Feat, playing “Long Distance Love.” Here, Dylan mirrors my translation of this line from “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”:

I play the gumbo limbo spirituals

In Chapter Six of “I Don’t Love Nobody,” published just a few days before Dylan’s first burst of Instagram clips, I showed how the lyric alludes to many of Dylan’s post-gospel period compositions (see my chapter for the details):

From “I and I” on Infidels, to “Narrow Way” on Tempest, Dylan … describes the distance between the narrator and his Savior, and a longing for reunion. These songs are “gumbo limbo spirituals.”

… just look for that telling combo: a narrator moving through a world ruled by “power and greed and corruptible seed” while holding the distant light of the promised land in his eye.

The key word here is “distance.”

I also wrote about how Dylan addresses God in his gumbo limbo spirituals:

Like the great Persian poets Rumi and Hafiz, Dylan often speaks to God as if He were a lover, but unlike those poets, Dylan writes from a country blues point of view, like a man forsaken. Combining Biblical language and vernacular phrases from old songs, the singer delivers tender tales that appeal to our romantic sensibilities, but more deeply, express feelings of spiritual loss and yearning.

I showed how this works in several songs, including the exquisite “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.”

Here’s the chorus of George’s “Long Distance Love”:

And no matter what I do

Even pray to heaven above

All I ever get from her is

long distance love

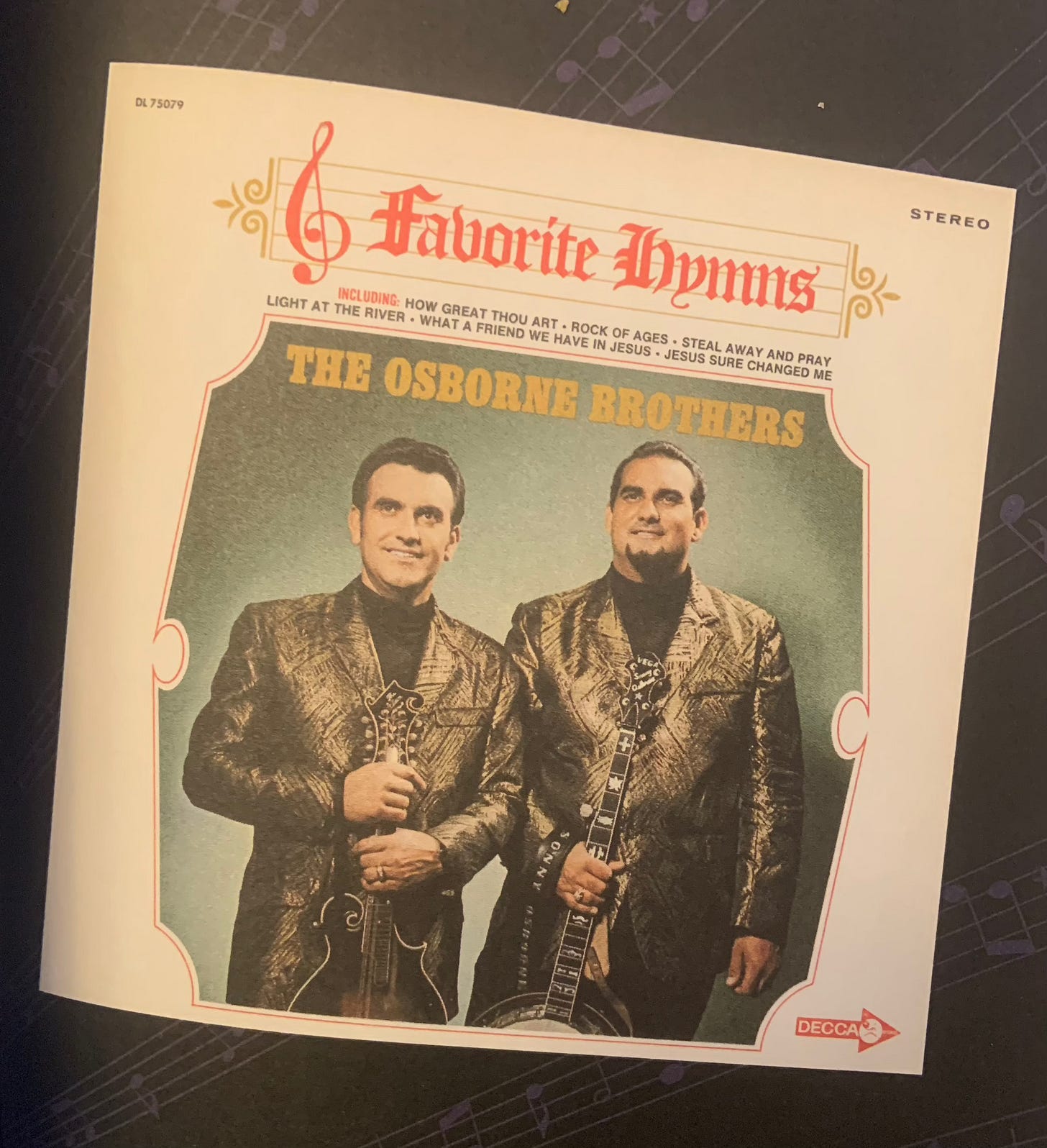

Next, we see the Osborne Brothers blazing through a rendition of “Ruby, Are You Mad at Your Man” from the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, as captured by Murray Lerner in his sublime documentary, Festival. This post is an intellectual funhouse of mirrors—to Rough and Rowdy Ways, my writing on the record, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” and Dylan’s musical life on “Mystery Street.” Bob is inviting us in; I’m pretty sure I can get you through and out the other side.

Festival is a documentary about Newport, but more specifically, it’s a film about folk music. It features performances by Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Odetta, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and many more, as well as excerpts from Dylan’s performances at Newport from 1963 to 1965. Lerner shows us not just the musicians on stage, but impromptu circles of players in the crowd. We see Dylan’s ‘65 electric performance of “Maggie’s Farm,” but significantly, Festival doesn’t present it as a seismic cultural shift or really, anything much out of the usual run of acts. Here we see Dylan’s plugged-in song as just another brilliant performance by an artist on the Newport folk stages. “Maggie’s Farm” is shown soon after a clip of Mississippi John Hurt playing “Candyman,” and directly after a older folk singer lady (whose identity I haven’t yet discovered) says:

I don’t know … what we call “folk” now, two or three hundred years ago, possibly was “pop.” We change.

Dylan’s performance stands in sharp contrast with Pete Seeger and Joan Baez singing “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” and the Staple Singers belting out gospel, but within Festival, it fits just fine. We also get acoustic takes of “All I Really Want to Do” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Recall, from Chapter One of “I Don’t Love Nobody” and from my last piece on the Instagram posts, how according to Dylan in Chronicles, a mention of a folk song is a reference to an underground story. Here, with a clip of the Osborne Brothers, Dylan alludes not just to a single otherworldly folk song, but to a film entirely about the otherworldly nature of folk music.

What can we take from this? What’s the underground story?

Let’s dive deeper.

Dylan includes an essay on “Ruby, Are You Mad at Your Man” in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Clearly, with this Instagram post, he intends us to have another look. He writes that “Ruby” is “close as it comes to alchemy” and “keen to drive you mad.” Luckily, we know from past experience where to go:

If you lost your mind, you’’ll find it there

Dylan writes that “Ruby” is “church Latin,” with “churchgoing harmony.” He adds that the Osborne Brothers were a “most high” bluegrass group and says that bluegrass is a music “steeped in tradition.” And then:

But people confuse tradition with calcification.

He goes on to describe how the Osborne Brothers changed their performance of “Ruby, Are You Mad at Your Man” over the years:

… the song morphed and grew. Drums were now part of the lineup and they found a way to incorporate them without gumming up the momentum. A throwaway lick played on the banjo one night was repeated and honed until it became a central riff underneath another part. It was still the same song but the tiny grace notes and elasticity kept it alive, shook the dust from its boots.

Of course, some people cried foul and those people should have stayed home.

Does this description of the Osborne Brothers remind you of someone else? All through “I Don’t Love Nobody,” I’ve described how Dylan alludes to his own experience through other voices. In a moment when the public eye is fixed on a movie that culminates with Dylan going electric, the artist posts a link that offers a mirror with a wider frame. In 1965, Dylan made an early leap in a career of artistic leaps. He was just getting started. Anyone attending a Dylan concert in the last forty years can testify that he continues to “shake the dust from [his] boots.”

In his Instagram post of the Osborne Brothers, the underground story is Dylan’s own life in song. We are back on “Mystery Street,” the rock and roll avenue of destiny and faith that runs from Duluth to “Key West” that I described in Chapter One of “I Don’t Love Nobody.” At Newport in 1965, the musician blew down some doors, but he never abandoned folk music. He merely abandoned the possessiveness of his audience and the restrictions of the ideologues.

In Chapter One of “I Don’t Love Nobody” and in “Bob Dylan’s Instagram Posts Part Two,” I showed how the unbound world of folk music remains central to the artist’s song composition. “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” features three traditional songs (and some tin-pan alley titles too). Recall that Elizabeth Cotten and Mike Seeger, who also appeared on the Newport stages and in Festival (Cotten just in an outtake), are key figures in the hidden story of the song. With his post of “Ruby Are You Mad at Your Man,” Dylan nods his head at my research.

Amazingly, this Osborne Brothers Instagram clip holds two more mirrors to Rough and Rowdy Ways, both found in the illustrations to the “Ruby” chapter in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Once again, Bob shows his fondness for a pun: the opening photo is a still from the famous clip of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. Two pages later, we get Ruby’s mug shots, and then in the text, Dylan riffs on conspiracy:

And then there’s Jack Ruby. Ruby, are you mad at your man—you could translate the song any kinda way. Ruby, are you mad at your man—well, I guess so. What’d you do that for?

This connects back to “Murder Most Foul,” in which Dylan infers that there’s more to the truth of the JFK assassination than the official version of events. The primary focus of his lyric, however, is a holy litany of late 20th Century song. All we know for sure about Kennedy’s murder is that “the age of the AntiChrist has just begun” and Wolfman Jack is “speaking in tongues.” As I described in Chapter One, concerning the murder of Bob’s friend John Lennon, when the heroes get gunned down, the only truth is found in the songs.

The final reflection between my writing on Rough and Rowdy Ways and the Osborne Brothers clip is seen in the photo at the top of this post: the illustration on the last page of the “Ruby” chapter of The Philosophy of Modern Song. On their Favorite Hymns LP, Bobby and Sonny Osborne, along with Red Allen, created gorgeous and transporting “churchgoing harmony.”

It’s all about the mirrors and the mirrors are all about the spiritual necessity of song.

Finally, Dylan’s last Instagram post is a scene from the 1956 film The Rainmaker, starring Burt Lancaster and Katherine Hepburn. This is my favorite of all Bob’s Instagram posts, the one that left me laughing at my kitchen table, because it provides the most direct answer to my request to Dylan for feedback, and the funniest. As you’ll recall, in my earlier posts, I wrote about how Bob puns on a crucial scene from The Golden Bird with the titles of films: Clash by Night and She Done Him Wrong. I first wrote about that scene, involving an incantation of song and a violent storm in the Colorado mountains, in Chapter Six of “I Don’t Love Nobody,” in my translation of Dylan’s term “Hindu rituals.”

In this clip, Bob Dylan responds to my query in the voice of Burt Lancaster. The actor plays a con man, Bill Starbuck, a rainmaker, trying to convince a family in drought-ridden Kansas that he can bring them relief. The patriarch of the family asks how Starbuck will achieve his magic. His response is pure poetry, which is part of the point, as the scene Dylan mirrors from The Golden Bird with his term “Hindu rituals” features the verse of T.S. Eliot, as well as one of his own lyrics. Here’s Lancaster’s soliloquy:

What do you care how I do it, sister, as long as it’s done? But I’ll tell you how I’ll do it: I’ll lift this stick and take a long swipe at the sky! And I’ll let down a shower of hailstones as big as cantaloupes! I’ll shout out some good old Nebraska cuss words and you turn around and there’s a lake where your corral used to be. Or I’ll sing a little tune, maybe, and it’ll sound so pretty and sound so sad, you’ll weep … and your old man’ll weep … and the sky’ll get all misty-like, and shed the prettiest tears you ever did see … How’ll I do it, girl? I’ll just do it.

Bob Dylan’s brain holds a lot of movie scenes. He chose a great one here to mirror my writing in “Hindu Rituals and Gumbo Limbo Spirituals” about the incantatory power of song. A chapter in which I shared my belief that the phrase “Hindu rituals” originated in an episode from The Golden Bird. I hope you can see why I take this scene from The Rainmaker as confirmation.

Thanks again for being here.