Prophets, True and False: Bob Dylan’s Search for the Holy Grail

Chapter Five of "I Don't Love Nobody": Hidden Stories from Bob Dylan's Rough and Rowdy Ways

Author’s Note:

Thanks for reading. This is a work in progress. Please begin at Chapter One, which has been revised extensively up until say, yesterday. I think the bits about John Lennon’s role in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” come through a lot more clearly now. The chapter below also includes many updates from the version I published last year.

I’m not making stuff up. All my work is based on the real stories behind Dylan’s imagery.

Please read in the App for the best experience and latest revision. Your email copy will inevitably include a typo and a clumsy phrase or two that I caught after pushing “publish.”

Long live Bob Dylan

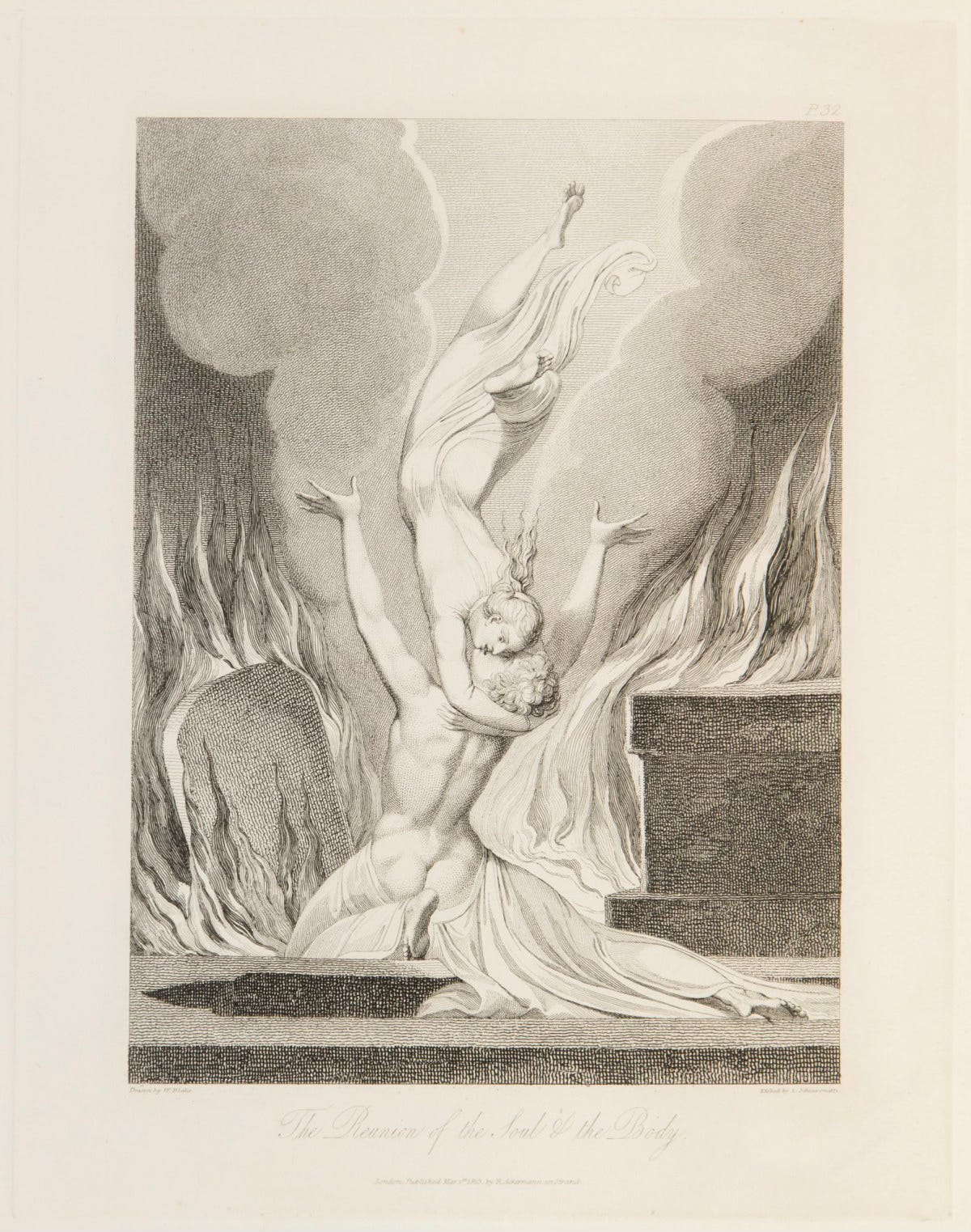

Imagination—the real & eternal World of which this Vegetable Universe is but a faint shadow & in which we shall live in our Eternal or Imaginative Bodies, when these Vegetable Mortal Bodies are no more

— William Blake

In this chapter I explore the allusions to prophets, true and false, that Bob Dylan includes on Rough and Rowdy Ways, a record whose main themes are faith and inspiration. In the track that addresses the concept directly, in the sixth verse, Bob exclaims:

I’ve searched the world over for the Holy Grail

I sing songs of love — I sing songs of betrayal

Don’t care what I drink — don’t care what I eat

I climbed a mountain of swords on my bare feet

In legend, the “Holy Grail” is the chalice used by Jesus at the Last Supper and then by Joseph of Arimathea to catch the Savior’s blood as He hung on the cross. Joseph—a “good and righteous man” according to Luke—was also the fellow who wrapped Jesus’s body in linens and laid Him in his own tomb, from which the Son of Man made a famous escape. He may also be the “Joseph from the Bible” that Bob said he would like to interview (along with Marilyn Monroe) in a 1985 magazine interview.

Poets of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries spun the Christian Grail story into Arthurian legend based on the premise that Joseph or his followers eventually carried the Grail to Britain. In 1920, Jessie Weston published From Ritual to Romance, a comparison of different versions of the Grail Quest. Her thesis is that the stories had roots not just in the Gospel, but also in pagan fertility rituals. T.S. Eliot, one of the prophets of Rough and Rowdy Ways, credited Weston’s book for the title and theme of his early masterpiece, “The Waste Land.” The wasteland is the territory of the Fisher King, keeper of the Grail, who has been rendered impotent, castrated in battle by a pagan knight. As a result, his realm is a barren place without fertility or beauty. The king is kept alive only by the presence of the Grail.

Eliot’s poem is, among many other things, a commentary on the stunted consciousness of humankind in the year 1922. He transferred the metaphor of the wasteland to urban London in the aftermath of the Great War, a place of mental fragmentation and spiritual decay, haunted by the ghosts of the dead. Citizens are beholden to the dictates of class, clergy, and capital, while nature and the true teachings of Christ are in retreat.

In The Power of Myth, a series of interviews with the journalist Bill Moyers, Joseph Campbell discusses the Grail and the wasteland:

The theme of the Grail romance is that the land, the country, the whole territory of concern has been laid waste … And what is the nature of the wasteland? It is a land where everybody is living an inauthentic life, doing as other people do, doing as you’re told, with no courage for your own life …

In a wasteland the surface does not represent the actuality of what it is supposed to be representing, and people are living inauthentic lives. “I’ve never done a thing I wanted to in all my life. I’ve done as I was told.” You know?

The Grail becomes the — what can we call it? — that which is attained and realized by people who have lived their own lives. The Grail represents the fulfillment of the highest spiritual potentialities of the human consciousness.

In the third verse of “False Prophet,” Bob gives his own spin on this idea:

I’m the enemy of treason – the enemy of strife

I’m the enemy of the unlived meaningless life

I ain’t no false prophet – I just know what I know

I go where only the lonely can go

In describing what it means to be “the enemy of the unlived meaningless life,” Bob calls out to a brother, Roy Orbison. In the last chapter I discussed how Dylan slyly comments on his own experience when, in Chronicles, he calls F. Scott Fitzgerald a “prophet,” twice. Here, similarly, by mentioning Lefty Wilbury’s 1960 hit, “Only the Lonely,” Dylan sends us back to his memoir for subtextual commentary. Bob writes about hearing Orbison’s “Running Scared” on the radio while he hung out in the mythical apartment of Ray Gooch and Chloe Kiel, and devotes nearly a full page to the imaginative power of his friend’s voice. Here’s a sample:

He sounded like he was singing from an Olympian mountaintop and he meant business … He sang like a professional criminal … His voice could jar a corpse, always leave you muttering to yourself something like, “Man I don’t believe it.”… next to Roy the playlist was strictly dullsville … gutless and flabby.

By itself, this quote shows Dylan’s regard for Orbison and why he might name drop Roy’s song into his song: I go where Lefty goes. But there’s more: a phrase in the passage takes us to another line in “False Prophet” and a second brother:

Hello Mary Lou — Hello Miss Pearl

My fleet footed guides from the underworld

No stars in the sky shine brighter than you

You girls mean business and I do too

Dylan draws a triangle from himself to Roy Orbison to Ricky Nelson. “Hello Mary Lou” means business; Roy and I do too.

Bob also cites the flip side of “Hello Mary Lou” in his beautiful ballad “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”:

Take me out traveling, you’re a traveling man

Show me something that I’ll understand

As with Orbison, Bob includes thoughts about Nelson in Chronicles. He recalls his impressions of “Travelin’ Man” as it played on the radio at the Café Wha?, and points out a mid-career shift in Nelson's music that led to boos from the audience. Dylan writes, "It turned out we did have a lot in common."

On Rough and Rowdy Ways, it’s always about the mirrors. Dylan, Nelson, and Orbison listened to their guides from the Underworld—their Muses—in search of the Grail. All are united as enemies of that unlived meaningless life. They mean business.

In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell explains that the Fisher King’s castration represents the separation in Christianity of nature from spirit. In the Grail legend, the health of the land and the King is restored when the innocent and naive hero, Perceval, finally attains the maturity to ask a Question: “Whom does the Grail serve?” Campbell says that the aim of the Quest, and the aim of the Question, is compassion, and reconciliation between heaven and earth:

That is to say, nature intends the Grail. Spiritual life is the bouquet, the perfume, the flowering and fulfillment of a human life, not a supernatural virtue imposed upon it.

And so the impulses of nature are what give authenticity to life, not the rules coming from a supernatural authority — that’s the sense of the Grail.

And here’s what Campbell, a professor of comparative religions and mythology, says when Moyers asks how we begin a conversation about love:

I’d begin with the troubadours in the twelfth century. The troubadours were the nobility of Provence and then later other parts of France and Europe. In Germany they’re known as the Minnesingers, the singers of love. Minne is the medieval word for love … You see, people didn’t know about Amor. Amor is something personal that the troubadours recognized …

The troubadours, he says, transformed the dualism of spiritual love—Agape—and sexual desire—Eros—into a love that could be experienced person to person:

The kind of seizure that comes from the meeting of the eyes

Bob Dylan has been singing about Amor for sixty years. And “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” the song that is the main subject of this book, may be his masterpiece on the unity of nature and Spirit: a tale of both human and divine love that takes place in a landscape of flowers and palm trees, at the very gate of Heaven.

Let’s look at the third line of the Holy Grail stanza again:

Don’t care what I drink — don’t care what I eat

This is an unambiguous reference to the words of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew:

Therefor I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, nor about your body, what you will put on. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing?

… But seek first the Kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be added to you.

Seek first the Holy Grail. Seek first the star that shines brightest in your life, the star that leads you on, the beacon that you know is holy:

Key West is the place to be

If you’re lookin’ for immortality

Stay on the road — follow the highway sign

Each night on the Rough and Rowdy Ways Worldwide Tour, the troubadour asked, on the stages of Albuquerque, Salt Lake City, and London, “Whom does the Grail serve?”

Most of the prophets on Rough and Rowdy Ways are musical artists, but as I showed in Chapter Three with the example of Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, some are movie stars. And from behind the piano in Phoenix, on the first show of the spring 2022 tour, he called out to another screen idol:

I wanna tell you something—that Arizona Biltmore hotel over there, it was Marilyn Monroe’s favorite swimming pool, anywhere! They got a park there, just in the spot she used to swim. Ha! We ALL swam there today!

All the boys in the band want to be close to Marilyn in her bathing suit —Amor, the driving force of life on Earth. Marilyn is another of the prophets of the LP. Here she is in “Murder Most Foul”:

Guitar Slim — Goin’ Down Slow

Play it for me and for Marilyn Monroe

On Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan gets a lot of milage out of Jimmy Oden’s song, cited here in a version by Guitar Slim. In “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” the phrase “goin’ down slow” brings up William McKinley’s prolonged death and “confession” through “Nearer My God to Thee.” In this couplet, Bob counterpoints the tragic demise of Marilyn—unable to find lasting love on Earth—with the dying president and his faithful wife, by his use of the same song. And once again, he includes himself, this time directly—an aged troubadour, making his last circuits of the world, confessing his faith, still singing Amor, and going down slow.

JFK, a very close friend of Marilyn’s, is another prophet of the album; Bob even calls him “the king” in one lyric of “Murder Most Foul”—a reflection of Jesus perhaps, but also of the Grail King and an emasculated culture—one that has been cut off from nature, a wasteland.

One of the most profound tellings of the Grail legend is Parzival, an epic poem written in the thirteenth century by Wolfram von Eschenbach. Here the naive young hero also fails to ask the essential question of the Grail King—in this version, “why do you suffer?” Because of his absence of compassion, Parzival is cast out of the castle. He comes to believe he is cursed by God, until an encounter with his uncle, the holy hermit Trevrizent, who convinces him to atone for earlier sins:

Say it to me if you got something to confess

See what I did there?

The hero is then able to return to the castle of the Grail King and ask the essential question. Eschenbach’s poem was the basis for Richard Wagner’s opera of the same name. The journey of Parsifal, on the quest for the Grail, reminds me of Dylan in the last two decades of the twentieth century, in the long undertow of his Christian absolutism, lamenting a distanced relationship with God.

The singer is tryin’ to get to Heaven, and the songs are his only guide:

Wolfman, oh wolfman, oh wolfman, howl

Rub a dub dub — it’s murder most foul

Wolfman Jack, he’s speaking in tongues

He’s going on and on at the top of his lungs

Play me a song, Mr. Wolfman Jack

In the art of Bob Dylan, very rarely is anything just one thing. Obviously the quote above refers on the surface to the disc jockey Robert Weston Smith, who famously spun the hits on a syndicated program broadcast on hundreds of radio stations across America in the 1970s and 1980s. Bob asks “the Wolfman” to play the litany of songs he then names in “Murder Most Foul.” But let me mess with Mr. Dylan’s lyrics just a bit:

Wolfram, oh Wolfram, oh Wolfram, howl

Rub a dub dub — it’s murder most foul

Wolfram Eschenbach, he’s speaking in tongues

He’s going on and on at the top of his lungs

Play me a song, Mr. Wolfram Eschenbach

Those opera singers do use lung power. The Wolfman/Wolfram connection might be a stretch, but the links go beyond a similarity of name. Recall the multilayered allusion to the fifth wound of Jesus, that “bleedin’ heart disease.” In Wagner’s opera, Parsifal heals the Fisher King by plunging a lance—the same one that punctured Christ’s side at the crucifixion—into his wound. His compassion restores fertility to the wasteland. The Grail is revealed, light fills the stage, and a dove descends. This latter is a symbol of the Pentecost and the ability of the apostles to “speak in tongues”—to convey the Gospel clearly in any speech; in this case, lyric poetry and deep-chested opera.

Dylan may or may not intend a reference to Eschenbach’s Grail poem, but in “Murder Most Foul” he clearly puts the preaching of the apostles into the playlist of Wolfman Jack. Song is a universal language, and as we know, song is Dylan’s holy lexicon.

In another chapter I make the case that Dylan also alludes, via T.S. Eliot’s spiritual poem cycle, Four Quartets, to the Pentecostal fire in his phrase, “the Hindu rituals.”

What are the meanings of true and false on Rough and Rowdy Ways? What is a false prophet? In playing a trickster, one who uses other artists’ words or chord progressions—F. Scott Fitzgerald or Billy Emerson or take your pick—to express feelings of heart and soul, yours and mine, Dylan complicates our picture of true and false. The imitator might be as authentic as the originator, or at least reach more ears. If I swing to Elvis Presley channeling Billy Emerson’s “When it Rains, It Really Pours,” am I denying Emerson’s genius or worshiping it? Have I been led astray, off the one true path, or am I coming closer to the Spirit of the Blues? If I scream along to John Lennon inhabiting Little Richard, am I a heretic or a simply a disciple in the Church of Rock?

Perhaps it’s the inspiration that counts—as I described in Chapter 4, Dylan values the company of the “transfigured.” These artists elevate us spiritually, help us in our search for the Grail, and lead us away from “the unlived meaningless life.”

Dylan seems to name a couple of “false prophets” in “My Own Version of You”:

Mister Freud with his dreams and Mister Marx with his axe

See the rawhide lash rip the skin off their backs

Dylan also disses Freud in Chronicles, saying:

There was a book by Sigmund Freud, the king of the subconscious, called Beyond the Pleasure Principle. I was thumbing through it once when Ray came in, saw the book and said, “The top guys in that field work for ad agencies. They deal in air.” I put the book back and never picked it up again.

I wonder, however, if Dylan particularly abhors Marx and Freud, or if they are in Hell because their words have been wielded by the craven, the corrupt, and the profiteers? Does Freud serve the devil, or is it the Mad Men at the ad agencies working for Lucifer, using a textbook of psychological tricks? Is that Satan lashing Marx, or does a power-hungry protégé, say Josef Stalin, hold the whip?

Maybe the followers are the deceivers. On Rough and Rowdy Ways, we are constantly urged to consider betrayal. Think of Brando, betrayed by his brother, a lackey of the Mob, in On the Waterfront. In all of his recent work, Dylan makes us question what is authentic and what is derivative. Who is honoring truth and who is practicing duplicity?

From “I Contain Multitudes”:

Greedy old wolf — I’ll show you my heart

But not all of it — only the hateful part

I’ll sell you down the river — I’ll put a price on your head

What more can I tell ya — I sleep with life and death in the same bed

“Sell down the river” means “betrayal.” Dylan threatens to turn the tables on a dealer in slaves. The phrase originated in the human markets of Louisville on the Ohio River, where all passages south led to grief and despair. We are reminded again of Dylan’s 2012 interview with Mikal Gilmore, in which, in response to a question about “citing [his] sources clearly,” Bob says:

These are the same people that tried to pin the name Judas on me. Judas, the most hated name in human history! If you think you've been called a bad name, try to work your way out from under that. Yeah, and for what? For playing an electric guitar? As if that is in some kind of way equitable to betraying our Lord and delivering him up to be crucified. All those evil motherfuckers can rot in hell.

Betrayal:

I’m the enemy of treason — the enemy of strife

Dylan contrasts the accusations that have been flung at him with the true meaning of betrayal. Selling people into bondage is betrayal. Denying the Lord is betrayal. Artistic change is not betrayal. Artistic change is creation.

A false prophet might be a newspaperman or a fan who can’t see beyond yesterday’s headlines. The Judas quote above reminds me of Bob’s anger at reviews of the first series of gospel concerts in the fall of 1979. He said the critics had no idea how to hear his new music, even though it was based on the most traditional of forms. Many times throughout his career, Dylan has been accused of betraying his audience, when he was truly being guided by tradition and his muse—by creativity. The artist’s followers are often the ones slinging insults, standing in the doorway, blocking up the hall. And it never ends. Constant as sunrise, you can find a newly published article bemoaning the loss of the old Dylan, complaining that the latest record just doesn’t do it for them like Blonde on Blonde.

As fans, perhaps we also have power to heal the land, if we might, instead of worshipping so mindlessly, ask of the “king”—JFK, Elvis, Dylan, John Lennon, take your pick—“why do you suffer?”

Rough and Rowdy Ways asks us, when thinking about truth, to consider the source:

Get lost Madam — get up off my knee

Keep your mouth away from me

I’ll keep the path open — the path in my mind

I’ll see to it that there’s no love left behind

I play Beethoven sonatas Chopin’s preludes … I contain multitudes

The narrator appears to suddenly think better of having invited a prostitute onto his lap. In the physical image of keeping her mouth away—her love for sale—he is rejecting what she has to say—her words. As always, cross-references between songs add perspective: in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” we find the mysterious allusion to the prostitute the narrator was forced to marry at age twelve. This seems to be a reference to an Old Testament Bible story, of an ancient time when God was angry that His people had forgotten Him. As the story goes, the Lord had Hosea marry a prostitute so that his prophet could understand betrayal—there we go again. God forced the marriage so that the prophet could learn to distinguish the truth from lies.

I don’t hear any denial of Judaism in the lines, quite the contrary. Dylan renounces nothing; he has “no apologies to make.” He will “keep the path open, the path in my mind.” Deep traditions—his birth religion and the music of the great composers—are the bedrock of his creativity.

Here’s another reference to being true to your calling, in “False Prophet”:

I’m first among equals — second to none

I’m last of the best — you can bury the rest

Bury 'em naked with their silver and gold

Put 'em six feet under and then pray for their souls

It’s easy to hear this only as a blues boast. It appeals to our egos and our hero-worship of Bob. That’s one level. Bob has a sense of his own cultural significance. You don’t take a line from Whitman—“I Contain Multitudes”—to describe yourself unless you are putting your art on the same level. It’s deserved, and no one would deny it. But in the first line above, we again hear Rimbaud’s “I am another.” Here Dylan channels his inspirations, from Charlie Patton to Leadbelly, all equals, all first, all second to “none.” He includes the great bluesmen and gospel singers who live under the “Blood-Stained Banner” in “Murder Most Foul”—a reference whose essential ambiguity I described in Chapter 3.

The word “none,” as Dylan uses it here, is a concept more subtle than it first appears: subtle in the precise sense that the word refers to the spiritual body. Dylan and all the other mortal gods of rock are “second” to the Spirit. Why do I say this? Because of the facts: the lyrics of Rough and Rowdy Ways abound with references to “none,” “nothing, and “nobody.”

Later in the song:

Put out your hand — there’s nothin’ to hold

Open your mouth — I’ll stuff it with gold

Oh you poor Devil — look up if you will

The City of God is there on the hill

There’s nothin’ to hold. The truth can’t be held by flesh, and your mouth—keep it away from me—is only good for speaking of earthly values—gold. Look instead to the City on the Hill. And:

I ain’t no false prophet — I’m nobody’s bride

Can’t remember when I was born and I forgot when I died

Nobody’s bride—the bride of no body. Famously, the bride of that spiritual Groom who is “still waiting at the altar.”

In Chapter One, I showed how these lines rephrase of one of the core teachings of the Bhagavad Gita. Here it is again in a modern translation by Carol Satyamurti:

Bodies are born, they flourish, age, and die.

But the soul, part of that greater spirit

That infuses everything that exists

Was never born and cannot be killed

Dylan cleverly rhymes the line from Hinduism with the Christian reference — “nobody’s bride.” The prophets are in agreement.

From “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”:

My eye is like a shooting star

It looks at nothing, neither near or far

And another one from “False Prophet”:

You don’t know me darlin’ - you never would guess

I’m nothing like my ghostly appearance would suggest

The physical self is mere phantom compared to the higher Self.

As minstrel singer Lew Sully put it in 1896, and Elizabeth Cotten sang in 1958:

I don't want to get married, always want to be free

I don't love nobody, nobody loves me

All they want is my money, they don't care for me

I don't want to get married, I just want to be free

And as Dylan rephrased in his song about “the enchanted land”:

I don’t love nobody — gimme a kiss

I don’t love no body. I love Spirit. And the kiss is otherworldly, from a “Pretty Little Miss” out of another folk song:

Fly around my pretty little miss

Fly around my daisy

Fly around my pretty little miss

You like to drive me crazy

But it’s okay if she does drive him crazy. The narrator is in the right place, in “Key West,” where:

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there

The Grail is the reconciliation of Spirit and Matter.

Recall my claim in Chapter One that a couple of the allusions above originate from an episode in The Golden Bird in which I have astral sex with a new devotee in the cult. If this transposition still seems far-fetched to you, despite the extended narrative I detailed, all mirrored in Dylan’s song, consider another prophet Bob has frequently invoked: the founder of Theosophy, Helena Blavatsky. As discovered by another researcher, Dylan nicked some of her lines for Chronicles Volume 1, and in Chapter Three I showed how the songwriter includes the Theosophist author of the Oz books, L. Frank Baum, in two lines of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” The term “astral projection’ was coined by Theosophists and the concept is a basic tenet of their belief system.

My memoir repeatedly features scenes set at the intersection of the material and spiritual worlds; I foreshadow this theme with epigrams set before the title page. First, from Rainier Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies:

Earth, isn’t this what you want, to arise with us, invisible?

And then, from the man himself:

You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal.

Several lines in “False Prophet” suggest that the narrator listens to teachings from many traditions, including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Theosophy, Show Business, and Folk Song. Here’s yet another couplet that contains the idea of the hidden nature of the soul:

What are you lookin’ at — there’s nothing to see

Just a cool breeze encircling me

Other researchers have pointed out that the second line is almost certainly from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a compilation of ancient texts that were intended to help a person’s journey through the afterlife, specifically the Duat, or underworld. Mary Lou and Miss Pearl can read aloud from the spells as we go. And of course, being dead, the narrator can’t be seen. He is now Spirit. Similarly, in “Mother of Muses,” the singer asks:

Make me invisible like the wind

In his search for the Holy Grail, the Song and Dance Man encounters so many prophets: Libba Cotten was also the author of “Freight Train,” which, in its “plagiarized” version by Brits Chas McDevitt and Nancy Whiskey, according to one account, influenced a young band, The Quarrymen—soon to be prophets. Cotten worked as a housekeeper for Ruth Crawford and Charles Seeger, and their children, Mike, Peggy, and Penny—a family of prophets. As I discussed in Chapter One, Dylan’s spiritual muse Mike Seeger first recorded Cotten and was a member of The New Lost City Ramblers, a folk band—prophets—famous for its covers of 78 rpm records of the twenties and thirties, recordings made by prophets, some of whom appeared on Harry Smith’s—a prophet—Anthology of American Folk Music.

In Chronicles, Volume 1, Dylan rhapsodizes about the effect Mike Seeger had on him in his early days in New York. He recalls seeing him perform in Alan Lomax’s loft:

… it dawned on me that I might have to change my inner thought patterns … that I would have to start believing in possibilities that I wouldn’t have allowed before …

I can’t give a better description of a prophet than Bob offers here. Mike Seeger led Dylan to the top of a hill and pointed to the horizon line.

About The New Lost City Ramblers, Dylan writes:

All their songs vibrated with some dizzy, portentous truth. I’d stay with the Ramblers for days. At the time, I didn’t know they were replicating everything they did off of old 78 records, but what would it have mattered anyway? It wouldn’t have mattered at all. For me, they had originality in spades, were men of mystery on all counts.

A prophet shows the way to truth and creativity. A prophet stands on the shoulders of those who have come before. A prophet lives on “Mystery Street.”

T.S. Eliot, as I mentioned earlier, is another prophet of Rough and Rowdy Ways. Mostly, Dylan’s fellow Nobel laureate appears obliquely, such as in the “Holy Grail” phrase, which leads us to "The Waste Land.” But the intertextuality between Eliot and Dylan is transparent in “Crossing the Rubicon”:

What are these dark days I see in this world so badly bent

How can I redeem the time — the time so idly spent

How much longer can it last — how long can this go on

I embraced my love put down my head and I crossed the Rubicon

The phrase “redeem the time” occurs in Part IV of Eliot’s “Ash-Wednesday”:

White light folded, sheathed about her, folded.

The new year’s walk, restoring

Through a bright cloud of tears, the years, restoring

With a new verse the ancient rhyme. Redeem

The time. Redeem

The unread vision in the higher dream

While jeweled unicorns draw by the gilded hearse.

The silent sister veiled in white and blue

Between the yews, behind the garden god,

Whose flute is breathless, bent her head and signed but

spoke no word

But the fountain sprang up and the bird sang down

Redeem the time, redeem the dream

The token of the word unheard, unspoken

Till the wind shake a thousand whispers from the yew

And after this our exile

In a 1935 letter to the composer Stephen Spender, Eliot described his poem:

Ash Wednesday for instance, is an exposition of my view of the relationship between eros and agape based on my own experience.

Elsewhere, Eliot says that the poem “aims to be a modern Vita Nuova.” This is Dante Alighieri’s poem that elevates the author’s love for Beatrice to the sacred — the same Amor we find in the marriages depicted in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).”

Eliot’s “silent sister in white and blue” is Mary. The scene takes place in a British church garden, indicated by the yews, but there is also a “garden god,” and we understand it is Pan. Through the reconciliation of these forces, Pan with his song of the seasons, and Mary, “through a bright cloud of tears,” bearing the sacrifice of the Lord—that “bleedin’ heart disease”—Eros and Agape come together in Amor.

The phrase “Redeem the time” originates in Ephesians:

See then that ye walk circumspectly, not as fools, but as wise, Redeeming the time, because the days are evil.

Once again we encounter the concept that we are called to make the most of our abilities—to live authentic lives and seek the Grail.

The third line in the stanza above is a well-worn gospel phrase, a plea for mercy and the Lord’s deliverance: “How long?” The troubadour has been asking the question for a while now. Way back in 1978, the women singing behind Bob on “New Pony” chanted over and over again, “How much longer?” in response to Dylan’s sexually suggestive wail of despair. In “Crossing the Rubicon,” the more mature poet still offers no answer, but now, like William McKinley, he embraces his love and crosses over—into the next song, into “Key West.”

Bob often writes about the garden. In 1980, he named a song after it. Here’s another citation from “Ain’t Talkin’”:

As I walked out tonight in the mystic garden

The wounded flowers were dangling from the vines

I was passing by yon cool and crystal fountain

Someone hit me from behind

An earthly garden can be a place of betrayal, as Gethsemane, or a place of beauty and communion. From “False Prophet’:

Let’s walk in the garden — so far and so wide

We can sit in the shade by the fountain side

Finally, in this discussion of prophets and betrayal, I’d like to return briefly to the idea that inspired this book, and the way my own path long ago became entangled with a prophet whom most would consider to be “false.” As I’ve described, I believe Dylan transposed elements from my memoir—particularly a forty-page section titled “Lightning Amen”—to his song. My exceedingly obscure book shows, among many other adventures, my activities in 1980, a year I spent wandering the highways of America with a messianic Christian cult, who were led by a “prophet” who claimed to be Christ returned. I never met the fellow, so I can’t say that I ever believed in him, exactly. But I did have a vision of Jesus, of a living breathing God, that filled me from top to bottom and inside-out.

Many years later, while writing my memoir with the resources of the World Wide Web at hand, I looked into this character. Scant information is available, but by the late 1980s it appears the group had disbanded. In 1987, the leader was sentenced to five years in prison for methamphetamine possession and he apparently died some time in the early 2000s. A few people online describe abuses cult members suffered at his hands. Other former followers dispute those assertions. I don’t know anything about these claims. As I said, I never met him and the group was decentralized to the point of the Center being Everywhere and also Nowhere. As you will see, if you read my book.

And what about cults? The word is a very fashionable negative right now, a term tossed around with abandon, to describe any group affiliation with a restricted way of thinking and acting. But cult is just another word for religion. Here’s what Bob has to say:

Corporations are religions. It depends what you talk about with a religion … Anything is a religion.

It depends what you talk about. There are cults and there are cults. There is Jim Jones, there is Trumpism, there are Methodists, there are Quakers. There are corporations. There is atheism. In 1978, just before his own conversion, Dylan himself seemed concerned with the belief systems that people become attached to, and entrapped by:

Socialism, hypnotism, patriotism, materialism

— “No Time to Think”

My cult was like none of these. Whatever it was to others, for me it was an authentic experience of spiritual mysticism.

I’m not saying it wasn’t crazy. It was. But it was a different kind of crazy than Scientology. It was more closely related to the kind of crazy practiced by St. Jerome, writing alone in a cave with a skull and a lion, translating the Bible. It was more closely related to the crazy of William Blake, who saw angels everywhere. It was more like the Shaker faith of Ann Lee, which advocated celibacy and nonviolence. It was more like the Christianity of Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, who, on trial for stealing from his father to rebuild the church of San Damiano—where Jesus had spoken to him from a wooden cross—stripped off his clothes, renounced all possessions, and began a life of ministering to the poor. After this he was known as Francis of Assisi.

But what about the prophet I followed? Was he “false?” From the facts I googled, we might conclude he was a charlatan, and that as a young man I was fooled and mentally abused. This is a compelling point of view. And the truth is, if not for my mother’s love and my family’s resources, my cult year might have led to worse outcomes. Some lives may have been ruined by joining the Christ Family and at least a couple were in fact ended—a friend sent me a news article about some members who were murdered on the road, and the same nearly happened to me. So perhaps Lightning Amen was a fraudster, tripped out by too much acid, and motivated not by Agape and Amor, but by Ego and Eros.

What is the alternative?

But the story I tell in The Golden Bird is not one of abuse and despair. My memoir is not a cult recovery self-help book. I am not concerned with exposing fraud, because I never experienced it as fraud, even if that fraud existed. I was a troubled young man and my memoir does not shy away from that fact. But The Golden Bird is a tale of faith and belief in an invisible God. My time walking the highways of America in my bare feet was a time of “innocence and purity.”

In his Quest, Parsifal eventually finds the Grail and heals the land. His defining characteristic is innocence.

What is true and what is false when it comes to inspiration? Shall I “betray” my experience by disavowing it? Did Lightning Amen lead me to despair or toward the Light? Was he like the Old-Time gospel singer from 2000 years ago or more like the folk covers band? Did He just play replications?

What would it have mattered, anyway? It wouldn’t have mattered at all.

Bob Dylan cites dozens of prophets on Rough and Rowdy Ways. I haven’t come close to mentioning them all. A moment ago I touched on Saint Jerome, who transcribed the Bible, but didn’t get to Bo Diddley, who had more earthly pleasures in mind in his song “Bring it to Jerome.” How about “Anne Frank, Indiana Jones, and those British bad boys The Rolling Stones?” Prophets, no doubt. And of course, Walt Whitman, who contained multitudes and was not afraid of contradicting himself. And William Blake, to whom visions of Jesus and the Angels were more real than anything in this “Vegetable Universe.” Blake, who, in “Auguries of Innocence,” gave Bob the line that closed nearly every evening of the Rough and Rowdy Ways Worldwide Tour 2021–2024.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an Hour

How about Bob Dylan himself? A prophet? I know one thing only. He ain’t no false one.

You are a beautiful writer. Thank you for these compilations and interpretations. 💋🌹❤️