Hello again. Today, my story is about Dylan’s Instagram post of the Louvin Brothers from May 13, singing their biggest hit, “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby.”

I also have thoughts to share about Dylan’s last two Instagram posts, “Al Capone in his own words, Parts Two and Three,” from May 20 and June 9. And not least, I’d like to offer my impressions about Dylan’s performance on his 84th birthday, at the Outlaw Music Festival in Ridgefield, Washington—my 60th Bob show over 47 years. To keep this piece from getting way too long, however, I’ll save these topics for next time.

As you know, crazy as it sounds, over the past four and half months I’ve been conversing with Bob Dylan on social media—he on Instagram, me on Substack—about the book I began publishing here in May of 2024: “I Don’t Love Nobody”: Hidden Stories from Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways. My book is about Dylan’s poetics on Rough and Rowdy Ways, and especially in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”—a song with several verses transfigured from episodes in my 2011 self-published memoir, The Golden Bird.

On Instagram, in an allusive language of musical performance, movie clips, and many puns, Dylan has concisely and humorously confirmed his transmutation of my passages into poetry. He’s also reflected my writing on the essential themes of his 2020 record. The first of these is mercy and compassion, the second is the way folk song reaches beyond a purely rational concept of reality, and the third is how song, delivered “live and in person!,” or through a small radio speaker, can hold incantatory and spiritual power.

Many of Dylan’s Instagram posts feature performance clips captured during his own high school years. Teenagers who are “searching for love and inspiration” are most open to the life-changing power of song. As I’ve shown, in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” and elsewhere on Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan alludes to episodes in his memoir, Chronicles Volume One, in which he describes his first glimpses of destiny. For the young Zimmerman, “Mystery Street” began at a Buddy Holly concert when he was 17; for me, it began at a Bob Dylan concert just after my 18th birthday; for a young person of another generation, it might begin at an MGK in-store performance.

[Author’s Note: On June 10, MGK released audio of Dylan narrating a trailer for his new album, “Lost Americana.” As you may have read, the two apparently met at Dylan’s Outlaw Tour show in Los Angeles. Some sources speculate that Dylan is supporting MGK because of a connection through his grandson. These stories are reported as big news, but they stay on the surface of Dylan’s art. In them, we are led to assume that Dylan’s Instagram shot of MGK exists in isolation from his other posts, and that Bob is just a grandpa sitting on his couch like you or me, sending random fan appreciation clips out into the Internet abyss. As this series shows, nothing could be further from the truth. Do we really believe that the greatest artist of the age, the one who expanded our conception of popular song, has no intent in his public messages beyond saying, “Eddie Van Halen! Cool! Also, check out this old movie!?” Dylan’s shout-outs to MGK, as unexpected as they may be, are not in themselves a creative act. And Dylan is ever creative. We might say, “that rascally old Dylan, always doing crazy shit,” but if we stop there, we are missing most of the real story.

For sixty-five years, crafting language and sound, Dylan has led us far from the mainstream, up tributaries, toward lost springs of culture. In “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” he takes us “beyond the sea,” to the “horizon line” of a mortal life. As I discussed in “Bob Dylan’s Instagram Posts Part 7,” his clip of MGK is a “Hindu ritual,” an example of the incantatory power of song, and as such, tied directly to his other posts. From the release of Rough and Rowdy Ways until today, Dylan has shown a tight unity of theme in his poetics, which includes the allusive language of his Instagram posts. That’s the hidden story. That’s the creative act. That’s the story I’m telling here, in “I Don’t Love Nobody.”]

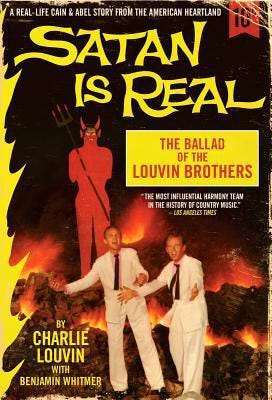

Dylan’s post of the Louvin Brothers is another mirror of the ideas I mention above. Charlie Louvin, the younger sibling, told the story of his life, and his brother Ira’s, with heart-piercing honesty in a 2012 memoir named after one of their best gospel records: Satan is Real. I’m guessing Dylan’s clip alludes to the entire world of musical inspiration revealed in Louvin’s book. Satan is Real offers one more memoir, one more “House of Memories”—as cited in Dylan’s post of the song by Warren Storm—for our philosophical pleasure.

The magic began for the Louvin Brothers—who were born as Ira and Charlie Loudermilk—with a voice coming over the airwaves in rural Alabama, when they were sixteen and fourteen years old. Every Saturday evening they would gather with local families in the yard of the shopkeeper, who had the only radio in the area, and take turns going into the house to listen to the weekly broadcast of the Grand Old Opry. One night, Charlie and Ira heard Roy Acuff announce a show coming to their very own school. On the appointed day, after their work in the fields was done, the brothers hurried to the concert and, because they were unable to afford tickets, listened to Acuff and his band through the open windows. Afterwards, they watched with admiration as the group departed in their expensive automobile, an “air-cooled Franklin.” Charlie and Ira were so impressed that they resolved at that moment to get off the farm and make a career as singers.

From the stage of the Grand Old Opry, Roy Acuff issued an invitation to Charlie and Ira Loudermilk to embrace their destiny. In the sweltering cotton fields of Alabama, the teenagers received the signal, clear as can be, over the pirate radio. Years later, Charlie and Ira would harmonize on that same Grand Old Opry stage, sending out their own songs over the radio, inspiring another generation.

In Satan is Real, Charlie tells about the long road to that stage. It began in a tough childhood filled with music. Colonel Monero Loudermilk worked his boys hard and was harsh with discipline—with Ira taking most of the blows—but he supported their gift for singing. After work, “he’d pick up his banjo and do three or four songs most every night.” Their mother, Georgiana, the daughter of a Baptist preacher, taught them songs she’d learned from her parents:

Her people were from a part of the world where a lot of folk songs come from, England, and we learned songs from her that most children wouldn’t ever have known. She raised us on those songs, singing them while she worked. And she was always working.

Probably my favorite was “Mary of the Wild Moor.” Ira and I learned it while helping her with her housework, before we were old enough to be out in the fields with Papa. Mama knew all those tragic songs, and she loved music.

On some weekends, their father would travel to Knoxville to sell vegetables, and he brought home records for the boys from a shop on the market street. Colonel Monero would also force the brothers to perform for guests in their home, and although they sometimes sang from under the bed, they eventually overcame shyness and stage-fright.

The Loudermilks traveled each year to a large family reunion organized by an aunt, where everyone joined in singing songs from the Sacred Harp, the 19th Century shape-note tune book. (Dylan recorded one of its loveliest songs, “Lone Pilgrim,” on his 1993 album, World Gone Wrong. I write more about that story in the coming epilogue to “I Don’t Love Nobody.”) Here’s how Charlie recalls the experience:

A Sacred Harp church ain’t like most churches. They don’t have any instruments, not even a piano. As soon as everybody made their way inside, the leader, who was this guy from Ider with a perfect ear, shouted out somebody’s name. Then that person stood up with their immediate family and walked to the middle, where they called out what song they was gonna sing, usually by page number from the songbook. Then the leader sang out the notes and gave a hum for the pitch, and we all stood up and laid into it.

That first song was electric. The whole church filled with the music of our voices. That was the first time I was really expected to sing along, but I joined in as easily as if I’d been doing it a hundred years. The human voice, that’s what they’re tallking about when they say Sacred Harp, and there’s nothing like it in the world. You can’t really record it either. Since everybody sings, it’s awful hard to get a microphone positioned so you can mix all of them. But it does your soul good to hear it.

Charlie also writes about Ira’s gift for copying singing techniques he observed at the Sacred Harp gatherings. One girl could sing “way up in the treetops, and then, just when you thought no human being could go any higher, her voice swooped down like a bird from the treetops, ran along the floor with us, and then soared again. It gave me chills.” Rising and falling harmonies, with changing parts, would become an astonishing part of the Louvin’s act.

My edition of Satan is Real has a subtitle that reads, A Real Life Cain and Abel Story From the American Heartland. That might be overstating things a bit. Charlie never killed Ira, but he did pummel him a few times. Ira was a drunk and while Charlie forgave many of the problems his drinking caused, he couldn’t overlook it when Ira insulted their mother. When Ira was soused, which was often, he lost his temper easily and screwed up many gigs. The clip Dylan posted on Instagram provides a case in point. According to Charlie, Ira’s actions at that session cost the group millions of dollars in lost royalties. The brothers were scheduled to perform more than fifty songs for a series of television shows, “Stars of the Grand Old Opry.” On the first day of filming, one of the crew told Ira that the shine on his mandolin interfered with the camera, so he’d need to paint it over. Ira, hungover from a bender and vain about his instrument (although he would sometimes destroy it on stage when frustrated, and rebuild it later) became abusive and told the camera-man to go to hell. As a result, the producer sent the band packing after they’d filmed only two songs: “I Don’t Believe You’ve Met My Baby” and ironically, one of their gospel hits, “Love Thy Neighbor.” Charlie writes that Ira’s alcoholism and rage were a reaction to his father’s beatings and also a self-inflicted punishment for not following his other calling, as a preacher.

Originally, the Louvin’s recording contract called only for gospel songs, released as singles. Eventually, however, they began to record secular material as well, and their first album, Tragic Songs of Life, contained several traditional tunes, including “Mary of the Wild Moor.” The murder ballad, “In the Pines,” also appears, a song recorded by many artists, including one alluded to in Dylan’s Instagram post of the rapper Proof: Kurt Cobain.

So many links exist between the story Dylan tells in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” his Instagram posts, my writing in “I Don’t Love Nobody,” and Satan is Real, that it’s hard to say which in particular he might intend, and which simply exist under the cosmic sky of folk song and musical inspiration. Here’s another example: the Louvin Brothers’ second record was named after the 19th Century hymn, “Nearer My God to Thee” and includes the song as the second track. In Chapter One, I wrote extensively about Dylan’s buried allusion to “Nearer My God to Thee” in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” The hymn is the “confession” and the “last request” of a dying William McKinley, and its lyrics tell the story of Jacob’s ladder from Genesis: a celestial staircase to heaven and the Biblical version of Dylan’s “Key West.”

Here’s another connection, involving some of the same musicians who’ve appeared in Dylan’s previous Instagram clips. Early in their career, the Louvins met a guitarist and promoter named Eddie Hill, and together they formed a group called The Lonesome Valley Trio. As I discussed in “Bob Dylan’s Instagram Posts Part Seven,” “Lonesome Valley” is the title of a song by the Carter Family and also a phrase that appears in Dylan’s song from the mid-90s, “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.” I showed how Bob’s post of the Carter Sisters and Johnny Cash singing “Were You There When They Crucified My Lord,” with its refrain “It made me tremble,” points directly to Dylan’s own 1979 quote about meeting Jesus: “I felt my whole body tremble.” In Satan is Real, Charlie tells how the trio were about to perform in Arkansas when he encountered a teenage boy standing outside the venue—dark-skinned from working the fields, dressed only in shorts. The boy had come to hear the music through the windows, just as the Louvins had done years earlier with Roy Acuff. Charlie invited him to sit on a bench just inside the door with his friends. Years later, when they met again, Charlie discovered the boy’s name: Johnny Cash.

Louvin tells another story about Cash from after the singer had become well-known, when they were all on tour with, you guessed it, the Carter Family. Charlie was going through a hard period and Cash loaned him a thousand dollars, for which he would never accept repayment.

In Dylan’s post of the Louvins, I can’t say if he intends an allusion to these tales about Cash and the Carters, buried deeply in Satan is Real, but they add more fascinating context to the “lonesome valley” lyric from his 1996 “gumbo-limbo spiritual,” “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.”

Finally, here’s one more connection between Louvin’s memoir and the story I tell in “I Don’t Love Nobody.” Again, I don’t assume intentionality on Dylan’s part in this detail; I’m just strolling down “Mystery Street.” Late in life, Cash recorded one of the Louvin’s biggest hits: “When I Stop Dreaming.” Here’s the chorus:

When I stop dreaming

That’s when I’ll stop loving you

As I’ve shown, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” features a dream in its penultimate verse—including three song titles which transfigure episodes from another memoir— which, once it stops, so does all the love.

Fly around my Pretty Little Miss

I don’t love nobody - gimme a kiss

Down at the bottom - way down in Key West