Chapter 3: The Bleedin' Heart Disease

Finding Mercy with Brando, Down in the Boondocks of "Key West"

In Chapter One, I described how “Mystery Street,” in Bob Dylan’s imaginary city of “Key West,” is a place of real and abiding faith, based in the biographies of Stephen Mallory, Harry Truman, Buddy Holly, and Dylan himself. “Mystery Street” circles from the shadows near the end of life, in a liminal “Key West,” to the places of Dylan’s beginnings, “not that far from the convent home” in Duluth. Early in the 20th Century, the Sisters of the Sacred Heart lived at the Sacred Heart Institute, just around the corner from the hospital they’d built, St. Mary’s, where Dylan was born on May 24, 1941. By the time Bob came along, the Sisters had moved to a new building outside Duluth proper, but they still worked at the hospital and walked the streets of his neighborhood. The Sacred Heart Institute became a residence for the St. Mary’s School of Nursing, where the students above are seen enjoying some down time. As you’ll notice, the photo is from 1937, which makes it possible that one of the young women pictured assisted in the birth of baby boy Zimmerman.

Also in Chapter One, I referred briefly to the Catholic devotion from which those Sisters took their name—the Sacred Heart of Jesus—and how Dylan alludes to it directly in this lyric:

The fishtail ponds and the orchid trees

They can give you the bleedin’ heart disease

People tell me I oughta try a little tenderness

In this chapter I look at that phrase more closely, along with related imagery, particularly the artist’s statement that his “Key West” is “down in the boondocks.” Unsurprisingly, knowing what a film buff Dylan is, we’ll meet Marlon Brando there.

To begin, what is the devotion of the Sacred Heart?

In the Middle Ages, Catholic mystics began to venerate the wounds Christ suffered on the cross. The practice of the Sacred Heart is focused on the Savior’s fifth wound, received when a soldier thrust his sword in Jesus’ side to see if He was dead. According to Church mythology, Jesus taught the devotion to a French nun in the 17th Century, in a series of apparitions. The Sacred Heart symbolizes Christ’s love and compassion for humanity.

Why might Dylan call the Sacred Heart a disease?

From “Ain’t Talking,” in 2006:

The suffering is unending

Every nook and cranny has its tears

When we feel compassion, our hearts bleed. We become a tiny bit more Christ-like. We suffer in empathy.

And here’s what he said in a 2014 interview with the AARP Magazine:

Q: What is the best song you’ve ever written about heartbreak and loss?

A: I think “Love Sick.”

What gives a person the “bleedin’ heart disease” in “Key West?” Dylan tells us it’s “the fishtail ponds and the orchid trees.” The fishtail palm is a species that flowers once in its life and then dies; in other words, it practices a sexuality that immediately results in death. The orchid is the most erotic of all the flowers, with hundreds of variations in its reproductive habits, and a wide variety of visual stimuli that have evolved to attract pollinators. Charles Darwin wrote an entire book about the sex life of the orchid.

Many people experience sorrow acutely in love relationships. The failures (and occasional delights) of romantic love are one of Dylan’s great themes, from “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” to “Love Sick” to “Long and Wasted Years.”

The wonderful fifth verse of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” holds a bittersweet image of romance, complete with another flower.

I got both my feet planted square on the ground

Got my right hand high with the thumb down

Such is life — such is happiness

Hibiscus flowers grow everywhere here

If you wear one put it behind your ear

Down on the bottom — way down in Key West

This stanza presents sexual love as a type of gladiatorial combat. In the ancient Roman spectacle, the producer of the games signified, by a thumb tucked down, that the defeated combatant should live: mercy. We know the battle is romantic because of the second triplet; in some tropical cultures, a hibiscus flower behind the year indicates if a woman is married (behind the right ear) or single (behind the left). After the bloodshed and the brutal blows of love, we hope and pray for mercy. Dylan’s world-weary delivery of the third line says it all:

Such is life — such is happiness.

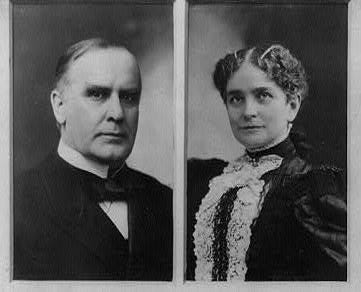

Marriage features repeatedly in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” In Chapter One I wrote about William McKinley’s assassination, as alluded to in Dylan’s revision of “White House Blues.” I described several of Dylan’s connections to “Nearer My God to Thee,” the hymn McKinley famously sang with his wife Ida as he expired. Biographers tell us about the couples’ deep devotion, emphasizing the President’s attention to Ida when her health declined later in life. Immediately after being shot, McKinley said to his aides, “Be careful how you tell her.” As William faded away from the sepsis that had overcome his body, Ida said, “I want to go too!” William replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours.”

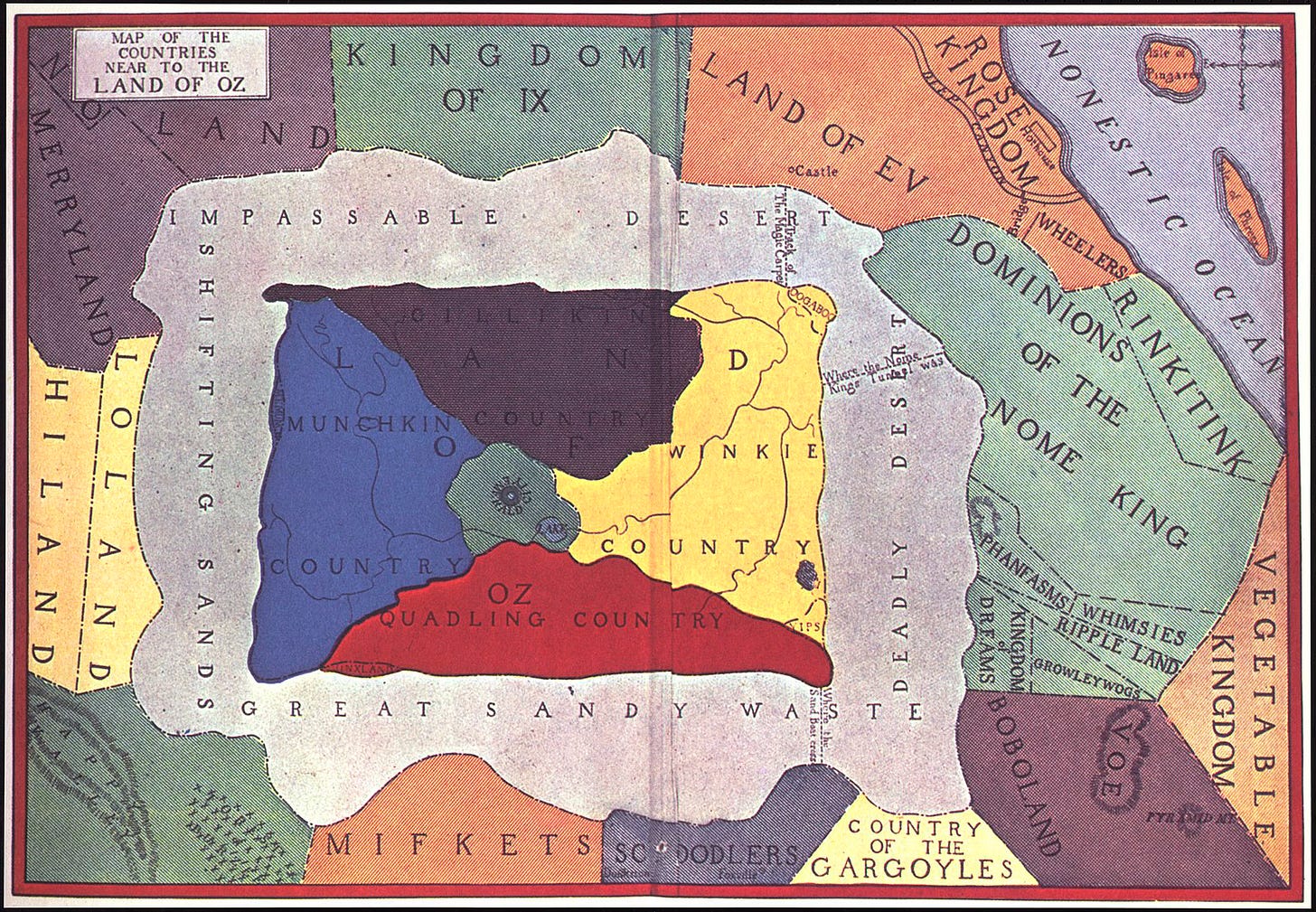

Frank Baum and Maud Gage, another loving couple who live between the lines in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” also suffered the “bleedin’ heart disease.” Allusions to Baum occupy succeeding verses in the song. First, Dylan sings that his imaginary city is:

Beyond the sea - beyond the shifting sand

As you can see, the only way to Oz is through the Deadly Desert, the Impassable Desert, the Great Sandy Waste, or across the Shifting Sands. In Baum’s famous story, Dorothy came in over the top, in a house whirled by tornado. In the following verse, however, the narrator of Dylan’s song says:

I’ve never lived in the land of Oz

Or wasted my time with an unworthy cause

L Frank Baum didn’t live in the land of Oz. As a child, four of his siblings died of diphtheria. From ages five until ten, he saw men leave for the Civil War, and if they returned at all, they came back disfigured. He married Maud Gage, the daughter of a pioneering suffragette, and the couple moved to Aberdeen in the Dakotas, where they lived industrious and creative lives. Frank worked as an actor, a shopkeeper, and a newspaperman before finding success as an author. The Baums believed in Theosophy, a religious philosophy in which all matter is alive and the dead are always close at hand, particularly the ghosts of children. So it’s not surprising to find Baum hanging out down on the bottom, near death in “Key West.” Dylan has shown a previous interest in Theosophy; researcher Scott Warmuth discovered that he borrowed material from a book by Helen Blavatsky, the co-founder of the Theosophical Society, and herself a famed borrower, for Chronicles Volume 1.

Baum put the hard realities of late 19th Century plains life into Dorothy's Kansas. It is “grey” in every direction. The land is “a grey mass,” Aunt Em’s eyes are “sober grey” and they are surrounded everywhere by the “great grey prairie. Uncle Henry never laughed … he was grey." Dorothy’s family struggled through a black and white land of worthy causes. In contrast, the Land of Oz blazed with brilliant color. In Oz, Baum created a world based on his belief in other realms and the fairy tales he loved, such as those collected by Andrew Lang. He dedicated The Wonderful World of Oz to Maud and while dying, he whispered to her, "Now we can cross the shifting sands."

Stephen and Angela Mallory were a pair of lovers from the early days of the real Key West. In Mallory’s biography, no doubt read by Civil War historian Bob, Angela stands out as Stephen’s muse. Stephen regarded her as “the most truthful and honorable being” he had ever met. They experienced joy and they suffered together. Five of their nine children died in infancy—the real city of Key West was not a place of healthful airs. In that age, yellow fever and diphtheria carried many young souls quickly back to their Maker. Angela and Stephen were left with the bleedin’ heart disease.

Another allusion shows the push and pull between physical and spiritual love. For a third time, Bob expresses his idea with a flower:

The tiny blossoms of a toxic plant

They can make you dizzy — I’d like to help ya but I can’t

Down in the flatlands — way down in Key West

The tiny flowers of the lily of the valley are lovely to look at but toxic to consume. The blossoms give their name to an old-time gospel number, also titled "I Have a Friend in Jesus," a song that takes its name from the opening of the Book of Solomon: "I am the Rose of Sharon and the Lily of the Valley." Christians interpret this line as a prophecy of the Christ, but the original text can make you dizzy with its sexuality. Dylan also referenced a certain Rose of Sharon—a woman that he might have married had the circumstances been different—in his gospel-era "Caribbean Wind" (a song, as you’ll recall from Chapter One, that also contains an allusion to "Nearer, My God, to Thee"). As with the orchid, the Rose of Sharon might give a person that “bleedin’ heart disease.”

Christian legend also tells us that the Lily of the Valley bloomed at the Holy Mother’s feet at the crucifixion, giving them another name: “Mary’s Tears.” She would have liked to help her Son, but she couldn't.

How do we survive the “bleedin’ heart disease?” Dylan points us toward song. Some are sacred, like “Nearer My God to Thee,” but some are secular, as he suggests in the third line of the triplet:

People tell me — I oughta try a little tenderness

According to the 1932 composition by Harry M. Woods, Reg Connelly and Jimmy Campbell, when your lover gets weary and full of grief, you gotta hold her, and you gotta use your soft words. We hear the message in the beautiful voices of Frank Sinatra and Otis Redding: you gotta show compassion and have mercy.

“Down in the Boondocks” of “Key West,” this last virtue is indispensable. Joe South’s song, mentioned at the end of the first verse, contained a chorus that was inescapable on AM radio in my childhood. Billy Joe Royal, the singer, asked the Lord to “please have mercy on a boy from down in the boondocks.” In 1965, the song sometimes alternated on the airwaves with the new Bob Dylan hit, “Like a Rolling Stone,” both of which were in the top ten on the charts that summer. South played bass on several tracks on Blonde on Blonde the following year. Once again in “Key West,” we find ourselves time-traveling through Dylan’s life and career.

The singer doubles down on the “boondocks” reference by including the song again in “Murder Most Foul”—the narrator asks the Wolfman to “Play ‘Down in the Boondocks’ for Terry Malloy.” Malloy is the conflicted dockworker in On the Waterfront who grieves his culpability in a murder. Ideas of compassion and mercy are the bedrock of this Elia Kazan classic. By alluding to the film, Dylan highlights a deeper level of the devotion of the Sacred Heart: being your “brother’s keeper.”

On the Waterfront tells the story of Malloy, a former boxer (we know Dylan’s history of interest in boxing) who unwittingly plays a part in a murder by corrupt union heavies, including his brother, of another dockworker who has agreed to testify to the Crime Commission. Terry (played by a luminous and gorgeous Marlon Brando) begins to awaken when he hears the social justice preaching of the local Catholic priest, Father Barry, and as he falls in love with his murdered coworker’s sister, Edie.

Three scenes portray themes that Bob mirrors in his reference to “the bleedin’ heart disease.” The first is a barroom conversation between Terry and Edie, who is back from college with the “Sisters” — in fact, a “convent home” — for the holidays, when her brother Joey is murdered. Edie cuts through Terry’s protective outer shell with her kindness. Terry says she probably doesn’t care about his hard-luck story, his tough background, and she says, “Shouldn’t everybody care about everybody else?” Terry calls her “a fruitcake,” and she says, “Well, isn’t everybody a part of everybody else?” Eva Marie Saint, who plays Edie, is an excellent actress, and we feel her compassion. Of course, at this point she doesn’t know the role Terry played in her brother’s death. When she learns that, Malloy must earn back her love and faith with a sacrifice that is unambiguous its depiction as Christ-like.

The second pivotal scene is Father Barry’s sermon on the docks. A longshoreman who was ready to break the “deaf and dumb” rule is killed, and Barry, played by a fierce Karl Malden, eulogizes him to the dockworkers and their corrupt bosses. He opens by saying, “Some people think the crucifixion only took place on Calvary. They better wise up!” He goes on to say the murders of Joey and the second dockworker were also “crucifixions.” Then, in a link to the “bleedin’ heart” of Dylan’s lyric that could not be more direct, he says that anyone who stands around and remains silent about these killings “shares the guilt of it just as much as the Roman soldier who pierced the flesh of our Lord to see if he was dead.” Father Barry goes on to say that Christ is with them every day on the docks and that every man working beside you is your “brother-in-Christ.” He asks what Jesus would say about the inequities and the murders and the silence, and as Terry Malloy listens, the viewer sees Brando’s eyes contort with guilt and revelation.

The third crucial scene is in the back seat of a car, with Terry’s thoroughly corrupted brother Charley attempting to save his own skin by talking Terry out of testifying to the Crime Commission. If he fails, he has orders to deliver his brother up to be killed. We think of Cain and Abel, and we think of Judas. When Malloy says he is considering testifying, Charley threatens him with a gun, but Terry disarms him with love and pity. Then Charley, for whom things are going straight to hell, reminisces about what a great fighter Terry might have been and blames his downfall on a bad manager. Terry reminds him that no, it was Charley himself who made him throw a fight to win a bet. “You was my brother, Charley. You should have looked out for me a little bit.” And then we get Brando’s famous line: “I could have been a contender!” Charley, chastened by truth, allows Terry out of the car. Next time we see Charley, he is strung up dead on a fence.

On the Waterfront tells of biological brothers who go the way of Cain and Abel and of disparate longshoremen who awaken to behave like brothers in Christ. It tells of lovers who only have a chance at happiness after Malloy’s “confession.” The images of the “bleedin’ heart disease” that Dylan includes in both “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” and “Murder Most Foul” show us that while earthly love is bound to break our hearts, “down at the bottom,” in “Key West,” we might find mercy.

“Down in the Boondocks” contains a second veiled reference to Dylan’s youth. In Sam Shepard’s 1987 interview with his friend, published in Esquire, which takes the form of a play, Shepard asks Bob if he felt “cut-off” during his childhood, “up in the Far North … in the boondocks.” Dylan replies by saying “Nah, ’cause I didn’t know anything else was goin’ on,” and then he sings the chorus of “Down in the Boondocks.”

Sticking with cross-references to “Murder Most Foul” for a moment, here’s the last line of the song that closes out Rough and Rowdy Ways, a lyric that relates directly to “the bleedin’ heart disease”:

Play the Blood Stained Banner — play Murder Most Foul

The “Blood Stained Banner” is a beautiful citation because it reconciles apparent contradictions. First, it likely refers to a song titled “We Are Soldiers in the Army” attributed to gospel singer James Cleveland. Also a pastor, Cleveland worked with many famous choirs and pop stars, including Billy Preston, Gladys Knight, and Aretha Franklin. The lyric says “We’ve got to hold up the bloodstained banner, we’ve got to hold it up until we die,” referring to a garment stained with the blood of the Savior. But the “Blood Stained Banner” is also the name of the last flag of the Confederacy. Dylan, in asking the Wolfman to play this song, takes us to visit both a Black Baptist church in the 1960s and a dying Confederate conscript in the 1860s. We see soldiers of the Lord fighting in the civil rights movement, and we see southern soldiers fighting for an unjust cause—like Stephen Mallory, and the narrator in Dylan’s great Civil War elegy, “’Cross the Green Mountain.” We feel compassion, that bleedin’ heart disease, for the oppressed and the enslaved, but also for the enlisted man caught on the wrong side of moral truth in a drama much bigger than himself. We see the descendants of slaves and the defenders of slavery, all subject to the judgment of Christ, under that Blood Stained Banner. And, to top it all off, we perceive the direct historical relationship between the events of the 1860s and the assassination depicted in “Murder Most Foul.” The same evil is still alive in America. It was not expunged by the Emancipation Proclamation, the Civil Rights movement, or the Voting Rights Act. In Dylan’s song, that evil is concentrated into a few seconds of mayhem in Dallas, and it has given birth to a new age—not Aquarian, but Anti-Christ:

They killed him once, they killed him twice

Killed him like a human sacrifice

The day that they killed him, someone said to me, “Son,

The age of the anti-Christ has just only begun.”

It’s comfortable to see Dylan’s mention of “the anti-Christ” as just another bizarre reference in a song filled with them. But it’s more accurate and meaningful to see it as a direct reference to his own experience—and to take him at his word. A young Bob Dylan, in November 1963, hears a voice that calls him “son”—perhaps the voice of an old man singing a song called “Murder Most Foul.” A story “only begun” on a dark day in Dallas is still happening in 2024. A singer looks in the mirror and sees himself, baby-cheeked. A singer looks in the mirror and sees himself, wizened.

From the New York Times interview on the release of Rough and Rowdy Ways:

To me it’s not nostalgic. I don’t think of “Murder Most Foul” as a glorification of the past or some kind of send-off to a lost age. It speaks to me in the moment.

As I write this morning in Seattle, Dylan is getting ready to take the stage at the Royal Albert Hall in London, for the very last show of “The Rough and Rowdy Ways Worldwide Tour, 2021-2024.” I doubt the lucky audience will hear “Murder Most Foul,” but they will get one more version of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” On recent recordings, Dylan delivers the song with minimum accompaniment, emphasizing the importance of the words with exquisite phrasing. Tonight, once more, Dylan will take us “beyond the shifting sands” with Frank Baum and Maud Gage, to “Mystery Street” with Stephen and Angela Mallory, and nearer, my God, to thee, with William and Ida McKinley. With these loving couples at his side, he’ll ask us all:

Say it to me if you’ve got something to confess

And then one last time he’ll offer his own:

In the time of my confession, in the hour of my deepest need

When the pool of tears beneath my feet flood every newborn seed

There’s a dyin’ voice within me reaching out somewhere

Toiling in the danger and the morals of despair

Don’t have the inclination to look back on any mistake

Like Cain, I now behold this chain of events that I must break

In the fury of the moment I can see the Master’s hand

In every leaf that trembles, in every grain of sand

These days Dylan ends each concert with a prayer of faith, compassion, and mercy. He’s got that “bleedin’ heart disease.”