Bob Dylan's Pirate Philosophy

Chapter 2 of "I Don't Love Nobody": Hidden Stories from Rough and Rowdy Ways

On Rough and Rowdy Ways, Bob Dylan sings about his creative borrowing. He perpetuates it willfully and unapologetically by using Billy Emerson’s riffs on “False Prophet.” He satirizes it and practices it (taking a concept from Mary Shelley) in “My Own Version of You.” On these songs, he is circumspect with direct transference of lines from other works, but he still takes plenty. He borrows a Whitman phrase for “I Contain Multitudes,” adapts a Heraclitus quote within that song, and uses a tidbit from T.S. Eliot in “Crossing the Rubicon.” And in the lyric that is the subject of the last chapter, he recasts entire scenes from my memoir for his own poetic expression. He transmits his intentions in the song’s title and bestows upon himself a new moniker to go with all the rest: Pirate Philosopher—which appears to be another stolen phrase.

By the 2020 release of Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan’s career-long practice of “Love and Theft” had been well-documented by researchers and critics. Scott Warmuth’s blog Goon Talk is the essential source for facts about hidden subtext that Dylan includes in his turn-of-the-millennium compositions, from Time Out of Mind through Modern Times. He describes literary transpositions from obscure texts and from authors as diverse as Jack London and Henry Rollins into songs and into Chronicles, Volume 1. Richard Thomas’ book, Why Bob Dylan Matters, is another valuable resource. The Harvard professor tracks down many of Dylan’s allusions and line transpositions from classical literature. And we know that Dylan borrows sounds as well as words. Lewis Hyde, in Common as Air: Revolution, Art, and Ownership, cites the work of musicologist Todd Harvey, who describes how Dylan adapted traditional tunes for the melodies of some of his most famous early songs. Common as Air is about the effects of copyright law on the development of ideas, technology, and art, and one of Hyde’s many fascinating points is that had current restrictions existed when Dylan was just starting out, he would have had a much harder time publishing some of his most brilliant songs. He might have been sued for copyright violations by the sort of corporation that now controls his catalog.

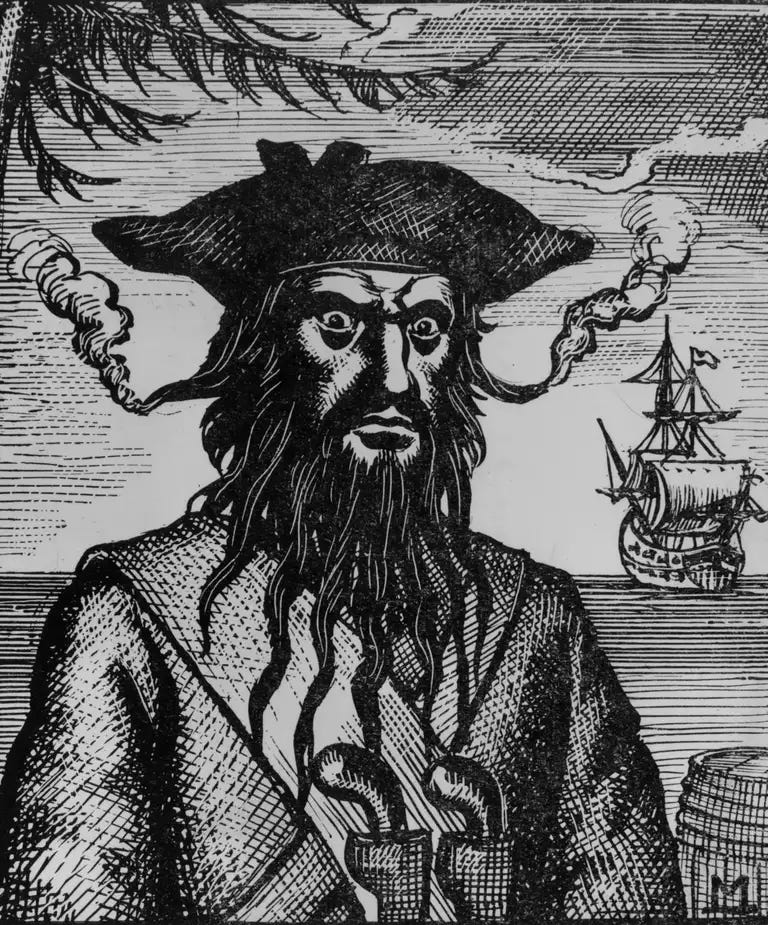

I’m sure most readers are familiar with the story behind “Love and Theft”: the musician borrowed the title of Eric Lott’s 1993 book for his brilliant 2001 album and even put it within quotation marks to acknowledge the allusion. Warmuth and others later uncovered dozens of line transpositions within the lyrics from literature and songs, famous and arcane—from a Japanese crime novel to a Minnesota travel guide. Researchers discovered similar pilfering on Bob’s previous record, Time Out of Mind. Lott’s book is an academic study of the racist art of blackface minstrelsy in which white performers, beginning in the 1830s, with a bizarre combination of envy, admiration, and condescension, imitated and adapted Black song, dance, and dialect, for working-class white audiences. Several authors have written extensively about Love and Theft and its relationship to Dylan’s album, including the historian Sean Wilentz in Bob Dylan in America and Dennis McNally in On Highway 61: Music, Race, and the Evolution of Cultural Freedom. McNally describes minstrelsy, with its appropriation of powerful Black song and dance, and its underlying sexual tension, as a potent liberating influence on repressed white America in the pre-Civil War years. He calls it “an endless succession of refracting mirrors.”

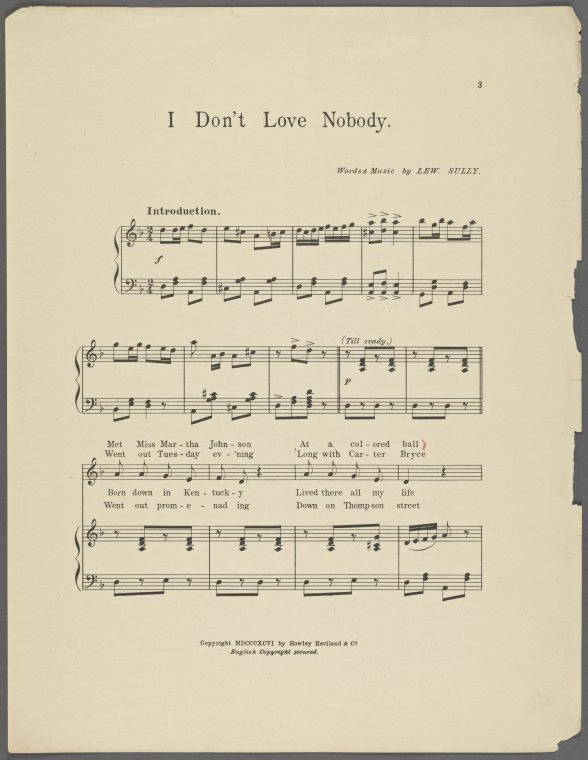

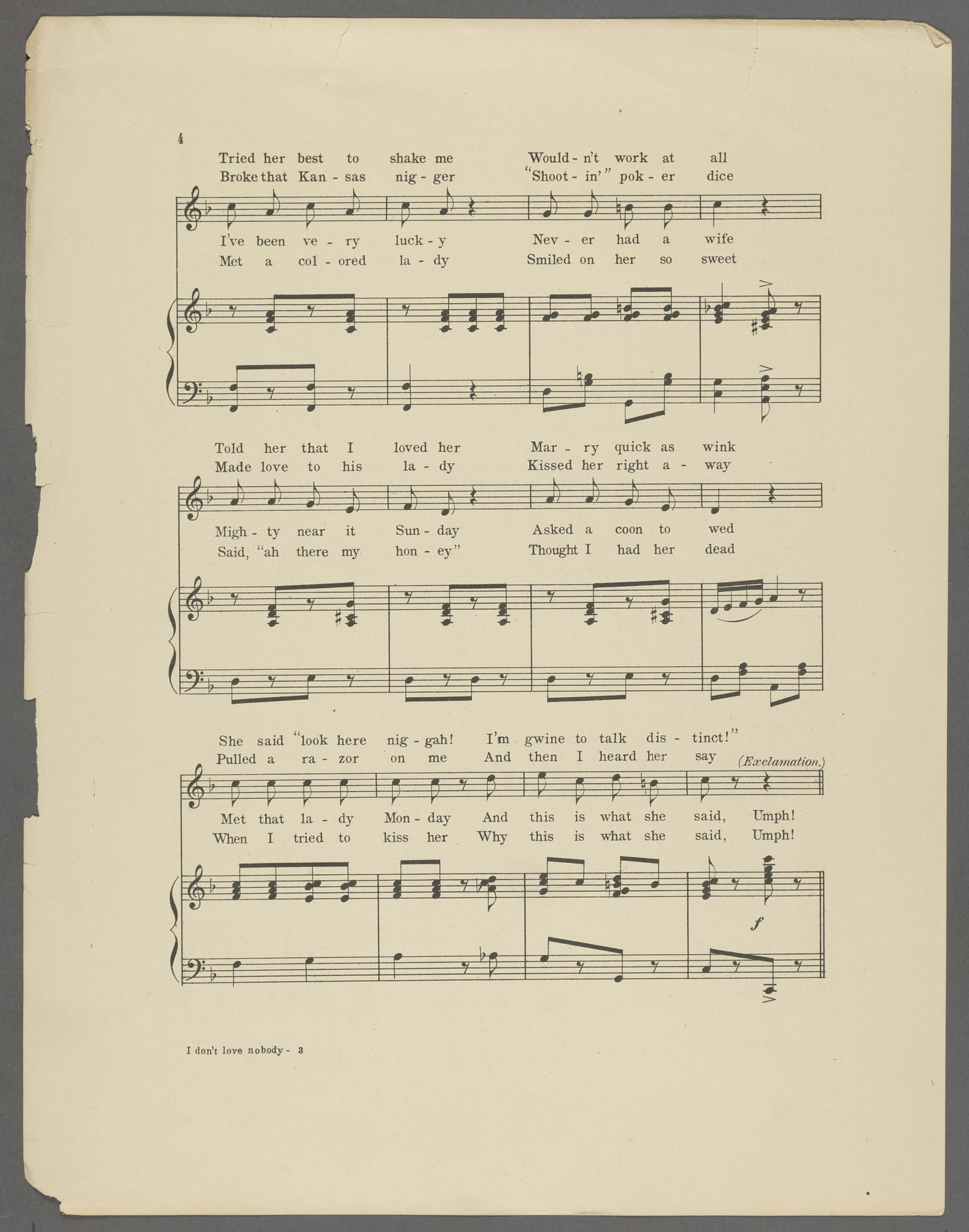

Minstrelsy, despite its racist nature and because of its fascination with the unbound creative force of African derived culture in America, was the original pirate philosophy. As of 2020, Dylan was still working with the “refracting mirrors” of the form. As I described in the previous chapter, the phrase “I don’t love nobody” for this book’s title is taken from his lyric in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” and the original source is an 1896 song by the blackface performer Lew Sully. In the 1950s, Elizabeth Cotten repossessed Sully’s racist lyric and turned it into a song of freedom. In “Key West,” Dylan honors Cotten’s change and also adapts the title as a poetic rephrasing of my disembodied spiritual romance in The Golden Bird. In doing so, the lyricist transfigures Sully’s words into a meditation on musical inspiration, death, and eternal love.

My tale about “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is merely the newest iteration of the oldest game Dylan plays. And part of the game is letting us know he’s playing it. Here I’d like to point out some recent subtextual references to his pilfering, beginning with one directly related to my memoir, and then share a few new examples of his creative piracy, beyond the transferences from The Golden Bird I detailed in the last chapter.

Dylan has a storied history of hijacking interviews for his own purposes; he speaks like his hero, Ali, once fought: ducking and weaving, evading, and sometimes striking out with a sudden jab. He uses these events to discuss his music on his own terms and we can never be quite sure if he is answering the question the interviewer posits or something else entirely. In Dylan’s last published conversation, with Jeff Slate for The Wall Street Journal, the musician subversively slips in a mention to his subversive practices. Between the lines, he asks the reader—as he said in the “Murder Most Foul” release announcement—to “stay observant.” Here’s what he said to Slate in response to a question about how he finds new music:

I’m a fan of Royal Blood, Celeste, Rag and Bone Man, Wu-Tang, Eminem, Nick Cave, Leonard Cohen, anybody with a feeling for words and language, anybody whose vision parallels mine.

Waterloo Sunset is on my playlist and that was recorded in the sixties. “Stealer,” the Free song, that’s been there a while too, along with Leadbelly and the Carter Family.

I don’t doubt Dylan’s sincerity about most of music on this list and the other artists he names in the extended quote. But what’s up with ““Stealer,” the Free song?” Have a listen. It is the most banal of early 70s rockers. Can this tune and band possibly have a place in Dylan’s pantheon beside Leadbelly and the Carter Family? Here’s the last couple of verses, containing the gist of the song’s lyrical concerns:

I gotta steal your love away

Steal your love, steal your love, steal your love

I gotta steal your love

I gotta steal your love

Steal your love, steal your love, steal your love

I gotta steal your love

Do these lines show “a feeling for words and language?” It’s no “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Where is “a vision that parallels” Dylan’s?

“I gotta steal your love, steal your love.” By “Free.”

Here’s the parallel: “Love and Theft.”

Something is happening here. Why does Dylan insert this allusion to his artistic methodology into a list of artists he admires?

From the opening pages of my memoir, as I am on my way to Dylan’s show at Blackbushe:

As we came up from the Tube into Waterloo, I hummed a few bars of an old Kinks hit, “Waterloo Sunset.” I vaguely knew that some old battle had given the station its name, but in my mind, rock and roll had made it famous.

Dylanologist Derek Barker, in his pamphlet, “A Picnic Surprise,” tells how Bob also took a train (a private carriage) from Waterloo and back again after the show.

I believe Dylan’s citation of “Stealer,” the Free song, next to a mention of “Waterloo Sunset” is a reference to his borrowings from my memoir. Call me a fantasist but I’m confident that when a well-thumbed copy of The Golden Bird turns up one day in Tulsa I’ll be called observant.

The artist seems to have a particular affinity for recycling the works of academics. The case of “Love and Theft” is plain. Here’s another example. Recently I read Timothy Hampton’s excellent 2019 book, Bob Dylan’s Poetics: How the Songs Work, and I was struck by a couple of correspondences between his text and items that have popped up in Dylan’s art. Hampton’s opening chapter, “Containing Multitudes: Modern Folk Song and the Search for Style,” eloquently analyzes the singer’s techniques of language in the early songs. Hampton uses Whitman’s phrase from Leaves of Grass, “I contain multitudes,” to describe Dylan’s remaking of folk song through a combination of voices, for example, how his use of old-time rural dialect early in “With God on Our Side” adds power to the standard English, intellectual conclusion of the song. Now, many people take inspiration from Whitman, and the phrase “I Contain Multitudes” is certainly famous, so of course Dylan’s song on Rough and Rowdy Ways could be coincidence. A journalist published a well-received popular science book in 2016 with the same title. Dylan’s song, however, shares a theme with Hampton’s analysis; both are about the voices he inhabits. “I Contain Multitudes” lists Poe, William Blake, the Irish poet Antoine Ó Raifteiri, Beethoven, and Chopin, just to name the easily apparent ones. Was Hampton’s book an inspiration for the song? Did Dylan take Hampton’s Whitman metaphor and run with it?

A second example from Hampton is more curious still. Chapter 6 of Bob Dylan’s Poetics is called “A Wisp of Startled Air: Late Style and the Politics of Citation.” Here, the professor discusses Dylan’s use of borrowed expressions to add subtext and resonance to the songs. He peels the layers of the verse and shows how in a single couplet Dylan can link characters and voices from entirely different eras. The chapter title, for example, refers to a line from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Dylan took some nearby and related dialogue from that novel for “Summer Days,” from 2001’s “Love and Theft” (Fitzgerald’s quotes in italic):

She’s looking into my eyes, she’s holding my hand

She’s looking into my eyes, she’s holding my hand

She says, “You can’t repeat the past.” I say, “You can’t? What do you mean,

you can’t? Of course you can.”

Hampton shows that in his song Dylan replays Fitzgerald’s theme of a character “grasping for the past” in a search for “lost loves” and “lost language.” In Fitzgerald’s words:

an elusive rhythm, a fragment of lost words

The author describes how this citation conjures in our minds not just Gatsby, but the famous Fitzgerald reference from “Ballad of a Thin Man,” in which Dylan ruthlessly satirizes establishment values, journalism, and the world of Academia:

You’ve been with the professors

They’ve all liked your looks

With great lawyers you have

Discussed lepers and crooks

You’ve been through all of

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books

You’re very well read

It’s well known

And so, ironically, the reference to Fitzgerald recalls own Dylan's lost past and revitalizes his critique from the sixties, even as it questions the value of looking back. Hampton, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, goes on to use the idea of “fragments” as a descriptor of the phrases the artist picks up from other works and from cultural history that add such depth and complexity to the songs. He shows how Dylan’s use of this language accentuates the sense of personal and societal “fragmentation and loss” that pervades the songs on “Time Out of Mind” and “Love and Theft.” He says:

Dylan shows us here that poaching—cultural poaching— may be the only possible solution to life in a world of ruins.

Hampton’s book is a great read. My purpose here, however, is not to replay his points, but to highlight Dylan’s possible creative thievery from Hampton’s description of his creative thievery. The artist’s most recent release from the Bootleg Series is Volume 17: “Fragments—the “Time Out of Mind” Sessions, 1996-1997.” Did Dylan poach his title again (actually, Fitzgerald’s phrase) from a writer who so beautifully describes the effects of his poaching? If so, how might we read between the lines? I see an appreciation of Hampton’s thesis. I see another refracting mirror of “Ballad of a Thin Man,” with its ruthless take-down of all those who perceive only the surface of things.

Or is Dylan’s title for the Bootleg Series featuring the very songs that Hampton discusses (yet more) mere coincidence?

Let’s return for a moment to Dylan’s interview with The Wall Street Journal. Jeff Slate:

[Philosophy of Modern Song] makes it clear that you’re a true fan of most of the artists included. But are you able to listen to music passively, or do you think maybe you’re always assessing what’s special—or not—about a song and looking for potential inspiration?

Dylan (my italics):

That’s exactly what I do. I listen for fragments, riffs, chords, even lyrics. Anything that sounds promising.

That’s exactly what he does. And what he does not do is choose words idly. As he sings in “My Own Version of You,” a song about creating a creature from found parts:

You know what I mean - you know exactly what I mean

But “fragments” is common word, it’s true. So we also need to consider T.S. Eliot. The Waste Land, his superbly horrifying masterpiece of the early 20th Century, also mines a wide swath of cultural history for allusions—from pub conversation to Vedic chants—and summarizes the technique in one of its final lines:

These fragments I have shored against my ruin

Eliot is all over Rough and Rowdy Ways. He is alluded to in the phrase “redeem the time” in “Crossing the Rubicon,” which comes from “Ash Wednesday.” I’ll discuss that one in another essay, and also show how the poet opens a cosmic portal between certain “Hindu rituals” and The Golden Bird via his spiritual masterpiece, Four Quartets. Later I also explain how Eliot accompanies Dylan on his search for the Holy Grail, as described in “False Prophet.” So, like “Stealer,” the Free song, Eliot seems to be very much on Dylan’s mind. Just as the Fitzgerald theft in “Summer Days” takes us to “Ballad of a Thin Man,” the superlative and bleak outtakes from “Time Out of Mind” on “Fragments” might summon the memory of the expatriate American in “Desolation Row,” fighting with his pal and editor Ezra Pound in the captain’s tower, perhaps over a comma, as the Titanic leaves the harbor, while Pete Seeger tries to start a sing-along:

“Which Side are You On?”

So … did Bob get the title for his rerelease from Professor Hampton, from Eliot, or both? In either case, the themes of ruination and pirating apply.

Why does Dylan take from the critics? (Eliot also was a critic.) Is it simply because he appreciates the work, or is something else at play? Let’s look at another example.

Gary Hall is an instructor who works at Coventry University in Britain, and his job title is “Research Professor of Media and Performing Arts, and Director of the Centre for Disruptive Media.” In 2016, he published a book titled Pirate Philosophy for a Digital Posthumanities, intended for an academic audience. Hall’s ideas describe Dylan’s habits perfectly. From the preface:

In the chapters that follow, Pirate Philosophy proceeds to ask how, when it comes to our own scholarly way of creating, performing, and sharing knowledge and research, we can operate in a manner that is different, not just from the neoliberal model of the entrepreneurial academic associated with corporate social networks such as FaceBook and LinkedIn, but also from the traditional humanist model that comes replete with clichéd, ready made (some would even say cowardly) ideas of proprietorial ownership, authorship, the book, originality, fixity, and the finished object.

Dylan, from 2012, jabbing hard with his own take on cowards:

As far as Henry Timrod goes, have you even heard of him? Who’s been reading hm lately? And who’s pushed him to the forefront? Who’s been making you read him? And ask his descendants what they think of the hoopla. And if you think it’s so easy to quote him and it can help your work, do it yourself and see how far you can get. Wussies and pussies complain about that stuff.

At the opening of his first chapter, Hall includes this definition:

Pirate … from the Latin pirate (-ae; pirate) …

Transliteration of the Greek piratis (pirate)

from the verb pirao (make an attempt, try,

test, get experience, endeavor, attack …

In modern Greek … piragma: teasing …

pirazo: tease, give trouble

Did Dylan get his phrase “philosopher pirate” from Hall’s book? We can’t know for sure, but when the musician borrows from the classics and from critics he teases and gives trouble. He tests us and attacks convention. When Dylan takes from the academics, he plays a version of the same game he played in the sixties with reporters—the sort who became the subject of his bile in “Ballad of a Thin Man.” Dylan’s borrowings from academics are minstrelsy without the racism, comedic skits of both admiration and mockery. He takes their work, which is often based in his work, creates something new, and sends it back. Dylan manipulates interviews — from the mid-sixties press conferences when he ridiculed and cajoled the questioners, to the 2012 battle with Mikal Gilmore of Rolling Stone that I quote above — for the same reason. The interviews and steals from the professors are more “refracting mirrors.” They comment on the commentary. They force new thoughts about everything old.

Dylan’s interview with The Wall Street Journal feels as scripted as pro wrestling. It reads like the interviewer, Jeff Slate, submitted questions (perhaps with some coaching?) and Dylan answered them in writing. The ostensible subject was The Philosophy of Modern Song and sometimes the musician’s answers seem like outtakes from that work. Here’s an exchange with bearing on his relationship with writers who prophesize with their pens. Slate asks:

Some of the artists here had pretty colorful—and sometimes checkered‚ histories. What do you think of the current debate separating the art from the artist? Do you think a “weakness of character” can hold an artist back?

Dylan’s answer:

People of weak character are usually con artists and troublemakers; they aren’t sincere and I don’t think they would make good songwriters. They’re selfish, always got to have the last word on everything, and I don’t know any songwriter like that. I’m unaware of the current debate about separating the art from the artist. It’s news to me. Maybe it’s an academic thing.

Fantastic! Bob claims to live under a rock. He’s “unaware" of something that has been at the top of cultural news for the last decade. He himself has been accused of both misogyny, related to the new book, and something like fraud, because of some mechanical book signatures, and “It’s news to me” that some folks want to take Picasso off the museum walls because he could apparently be an asshole. Dylan dismisses all of this with “Maybe its an academic thing.” Ha! My translation: The question is so absurd as to not deserve an answer. Only wussies and pussies worry about that. Art is something artists do, not an academic conference. Again, we recall Mr. Jones. The academic world is useful but it’s a box. Nobel Prize? Hand me the Spark Notes, please. (If you don’t know this one yet, Dylan seems to have cribbed large parts of his Nobel lecture from the college study guides.) Art is not a matter of analysis, criticism or prizes. Art is subversive.

What is a “Philosopher Pirate,” anyway? He’s a “Stealer.” He thinks love is “Free.” He’s a thoughtful and intelligent person who happens to loot and plunder. The expression also reminds me of a “philosopher king,” the Platonic concept of a benevolent, knowledgeable ruler. A philosopher is a deep-thinking person — according to the Oxford Dictionary, “one who seeks wisdom or enlightenment” — who adventures and raids on the high seas of life. Bob once owned a schooner that sailed Caribbean winds from Nassau to Mexico (fanning the flames in the furnace of desire). Dylan is a pirate captain who hunts for gleaming metals he can liquefy in his forge and reshape into new songs. He is not the only pirate, not by a long shot, but he is the best — as he says in “False Prophet”:

Second to none - you can bury the rest

A Philosopher Pirate steals treasure and hides it for others to find and understand, if they can. He draws a map. And pirating is the shadow of its innocent twin, inspiration:

I’m searchin’ for love and inspiration

On that pirate radio station

It’s comin’ out of Luxembourg and Budapest

As I showed in the last chapter and as other researchers have documented, gold is buried between the lines of Chronicles Volume 1. Philosophy of Modern Song is some kind of different beast, one I can’t name, but it also contains subversive intent. Here’s an example. Chapter 26 is a short dream about Ray Charles’ 1954 breakthrough hit, “I Got a Woman.” The song has a complex history of appropriation. James Boyle, in his 2008 study of copyright law, The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind, claims that the composition, cited in some histories as a secular and sexualized adaptation of an old hymn, “Jesus is all the World to Me,” might instead be a copy of a contemporaneous gospel by Clara Ward, called, “I've Got a Savior.” Instead of loosely basing his tune on a very old song, it’s possible that Charles transposed his erotic soul flavors onto an original composition by the proven gospel hit-maker Ward. It’s plausible, because he also changed her most famous song, “This Little Light of Mine,” into “This Little Girl of Mine.” Peter Guralnick, on the other hand, in his essay “Cosmic Ray,” tells how Charles and his trumpeter Renald Richard heard “It Must Be Jesus” by the Southern Tones on the gospel radio while driving between gigs, and based "I Got a Woman” on that. Which in turn is a variation on the old spiritual, “There’s a Man Going Around Taking Names.” Whatever version of the story is true (I lean towards the latter because it is based on a first-hand interview), we know that by using piracy Ray Charles created something brilliant, something “new” and exciting that launched the next part of his career. Boyle points out that in today’s litigious environment and under current copyright law, originality of this sort might never happen. This is the same point that Lewis Hyde makes about Bob’s classic early songs. Dylan, with his expansive knowledge of musical history, is undoubtedly aware of the lineage of “I Got a Woman.” His essay is a funny riff about a man stuck in traffic on the way to his girlfriend’s house, where the magic seems to have died. The image across the crease is a cover of an old pulp magazine called Best Detective, subtitled True Fact. Can we know the “true facts” of a song’s history? Isn’t the history of songwriting a history of heavy traffic? How can the mystery of creativity survive when the money grubbers litigate chord structures? I bet Ed Sheeran would have an opinion.

Here’s another curious reference to artistic copying in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Chapter 47 is about Cher’s “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves,” written by Bob Stone. A few lines near the end:

Eventually Cher met and fell in love with Sonny Bono, an aspiring singer and actor. Sonny was a record producer, a protégé of Phil Spector’s, and went on to have great success singing with Cher. But his greatest achievement was as a congressman, where he helped pass the Sonny Bono act, which extended copyright terms for all songwriters.

While I acknowledge that Dylan is, as he says in “I Contain Multitudes,” “a man of contradictions, a man of many moods,” something smells off here. As Bob indicates, The Sonny Bono Act, also known as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, is the 1998 law that extended copyright an additional 20 years, to 70 years after the death of the author for most works. The derisive nickname refers to Disney’s intensive lobbying on behalf of the measure, so that their iconic character would not fall into the public domain, and they could keep milking that mouse (is that possible?).

I don’t have space here to discuss all the complexities of the copyright debate, but I recommend the books mentioned above, by Lewis Hyde and James Boyle, for an overview. In the meantime, allow me to simplify. The Sonny Bono Act is a vast overreach from the intention of the Constitution. It favors corporate ownership and hereditary wealth over the rights of the public to remix ideas. The initial term of copyright in the United States in 1790 was 14 years, plus the ability to renew once for 14 more. In the early 1800s the full term was extended to 40 years. In 1976, more than 140 years later, the period was extended to the life of the author plus 50 years, and the 1998 act added another 20 years. What began as a fair balance between the rights of creators to make a living from their work and the rights of the the public to advance ideas, has now become just another way for rich families and rich corporations to stay rich and get richer. According to Sonny’s widow Mary Bono, who was elected to his seat after his death, and who then helped push the law through Congress:

Actually, Sonny wanted the term of copyright to last forever.

Dylan praises Bono with a straight face, but the evidence I’ve included here indicates that he believes exactly the opposite. Why then would he make this comment? Again, we need to look beneath the surface. The piece about “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves” is all about the carnival and the con, illustrated by two separate pictures of barkers and the human wares they are selling. The third photo is of a vagabond, and it reminds me of a Dylan t-shirt I used to have for the release of Time Out of Mind, with a drawing of a tramp, all his possessions tied to a stick. This is the setting for Dylan’s statement, and here is what Jeff Slate asks Bob about the illustrations in Philosophy of Modern Song:

Would you like to discuss the significance of any of the artwork used in the book?

Dylan:

They’re running mates to the text, involved in the same way, share the same outcome. They portray ideas and associations that you might not notice otherwise, visual interaction.

Decide for yourself, but the “ideas and associations” I notice from these pictures is that the Sonny Bono Act is another con, sold to us, in the words of the 2012 Dylan song “Pay in Blood,” by:

Another politician, pumping out his piss

On the other side of the ledger, it’s true that Dylan recently sold his publishing rights and music catalogs to the same sorts of corporations I have mentioned here, that exist solely to suck the culture dry, but frankly, he’s an old man and needs to get his estate in order. His heirs will thank him. If there’s one thing worse than leaving tens of millions of dollars behind for your children, it’s leaving no arrangements so they need to figure it out. That’s the system we live in. And who knows what charities he silently supports with that cash.

I have one last item from The Philosophy of Modern Song to mention regarding artistic borrowing. At the end of Chapter 38, about “My Prayer” by the Platters, the artist lists a half a dozen pop songs which are “based on classical melodies” and another fourteen “with English lyrics based on foreign melodies.” The musician clearly implies that standards like “My Way” and “Catch a Falling Star” are not products of a single mind or a single time. Early in the essay, he traces the evolution of “My Prayer” from its beginnings as a 1926 French violin piece. Dylan then shares other songs about prayers, some of which he calls “merely pop songs.” Then he writes:

The greatest of the prayer songs is the Lord’s Prayer. None of these songs even come close.

In the previous chapter, I introduced you to my memoir and shared a few reasons why Bob may have been interested; here’s one more. I wrote that one of the main commonalities between my text and “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” are allusions to Christian mysticism. Bob’s favorite prayer song also appears twice in my story, in full—at the conclusion of the preface, just before the chapter at Blackbushe, and at the story’s dramatic culmination in Colorado. The Lord’s Prayer is a “Solid Rock” supporting my tale from beginning to end. It is a source of grace —as Dylan sings in another song he has played a lot lately—“in the time of my confession, in the hour of my deepest need.” It keeps me alive as I contemplate suicide while kneeling on the ground in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. I have a vision of angels. Close listeners to Rough and Rowdy Ways will recall an excerpt of The Lord’s Prayer in “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”:

For thine is the Kingdom, the Power and the Glory

Go tell it on the Mountain, tell the real story

Finally, one last take from Jeff Slate’s Wall Street Journal interview:

What style of music do you think of as your first love?

Bob Dylan:

Sacred music, church music, ensemble singing

There are no copyrights on hymns.